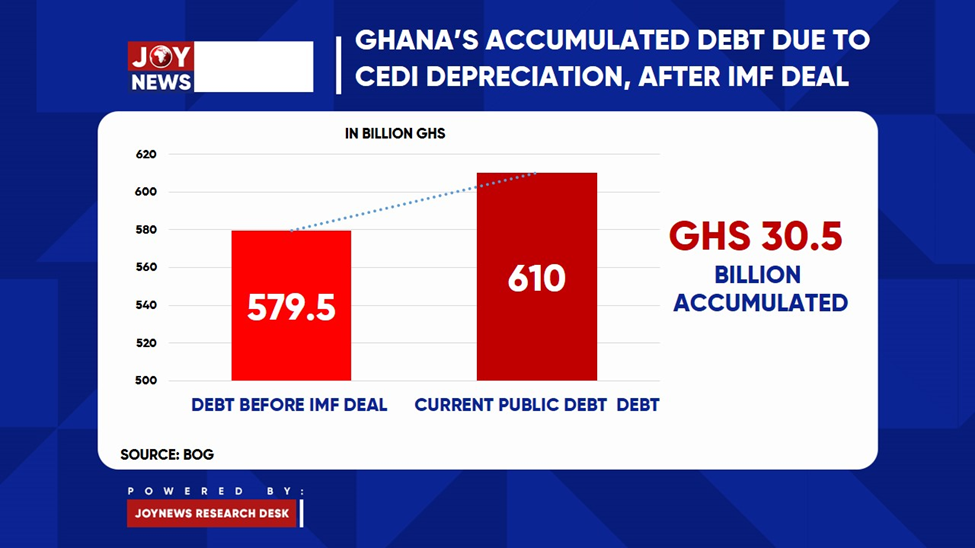

Data from the Apex Bank in Ghana indicates a growing disparity between the nation’s public debt before and after agreement on the $3 billion Extended Credit Facility from the IMF.

According to the Bank of Ghana’s March 2024 Summary of Economic and Financial data, debt accumulated from May 2023 (start of the IMF programme) to date amounts to GH¢30.5 billion (local currency); bringing the total public debt stock from GH¢579 billion to GH¢610 billion.

This is the highest in Ghana’s history.

The report also indicates that this debt accumulated due to the depreciation of the cedi.

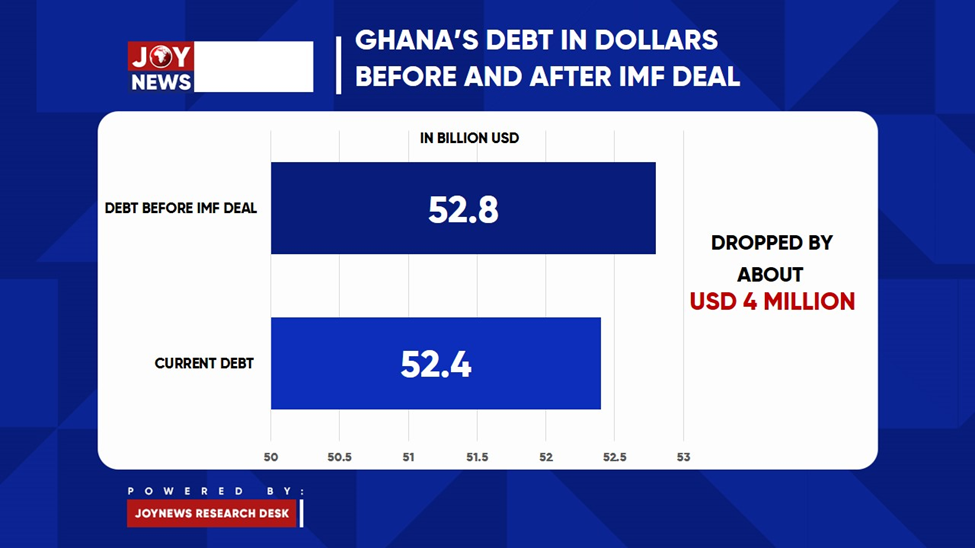

In as much as Ghana’s debt was increasing in terms of the cedi, it has decreased by about USD4 million in dollar terms.

There is a broader perspective to this if we are to go deeper in to why Ghana went to the IMF.

In 2022, Ghana encountered a significant economic crisis driven by internal vulnerabilities and external shocks.

Before COVID-19, Ghana’s loose fiscal policy relied heavily on expensive borrowing, compounded by challenges in the energy and financial sectors. The pandemic and global events exacerbated these issues, the culmination of tightening financial conditions, rapid escalation of debt levels, soaring inflation rates, substantial depreciation of the exchange rate, and the depletion of foreign reserves precipitated a full-fledged macro-financial crisis causing Ghana to lose access to international bond markets and leading to capital outflows.

To address funding gaps, the government increasingly relied on domestic borrowing, but high interest rates hampered private sector growth. Banks also became overly exposed to government debt.

Consequently, economic growth slowed, tax revenues declined, and investor confidence in Ghana’s currency stability and debt management weakened, hence the need to seek an IMF bailout to achieve sustainability in the economy.

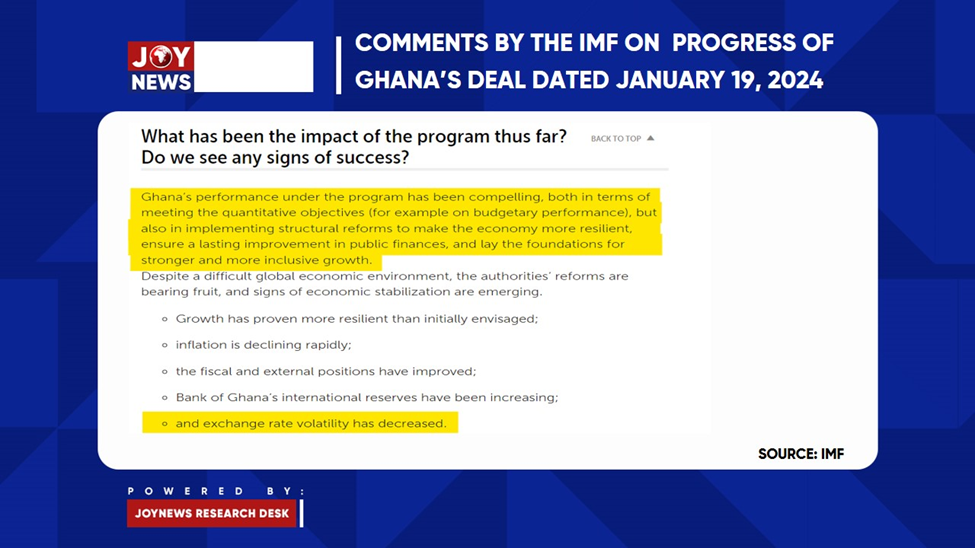

Fast-forward, the economic conditions started getting better after the deal with the IMF and resulted in some positive comments by the Fund.

Current indicators, however, seem challenging due to the increment in the exchange rate volatility.

According to Bloomberg reports, the cedi has lost close to 9% value in the first three months of 2024 making it the third worse performing currency next to Nigeria and Egypt.

This is partly due to the decrease in the nation’s trade balance for the first two months of this year (2024) to USD 392.8 million compared to the USD 862.5 million same time in 2023.

This represents about 54.4% decrease in trade forex this year compared to same time last year. This is driven by the decrease in cocoa revenue this year.

There is a delay in cocoa syndicated loan for the purchase of cocoa beans for exportation, which is also decreasing the size of forex inflows. The limited forex is causing pressure on the greenback hence the depreciation of the cedi.

Other developments such as the monetary tightening policy by the US and the spillover forex crisis in Nigeria are all contributing factors.

This, if not taken care of, could be very detrimental to the progress made from the IMF program.

Continuous depreciation of the cedi will lead to an increase in cost of import, which will translate into the cost of goods and services, thus rising inflation.

More debt will be accumulated due to the depreciation, leading to defaulting and other forms of economic challenges.

The question then remains absolute, what are we doing about it?