Finding a decent, affordable place to live is a common problem facing young people in many places. But in Nigeria’s booming commercial hub, Lagos, it is almost impossible as landlords demand a year’s rent in advance.

For two-bedroom apartments with electricity, close to the city’s main business district on Victoria Island, I was asked for between $11,000 (£8,600) and $22,000 upfront.

In general, middle-to-high-income housing can cost anywhere between $5,000 and $40,000 a year.

These are amounts of money that few people have available.

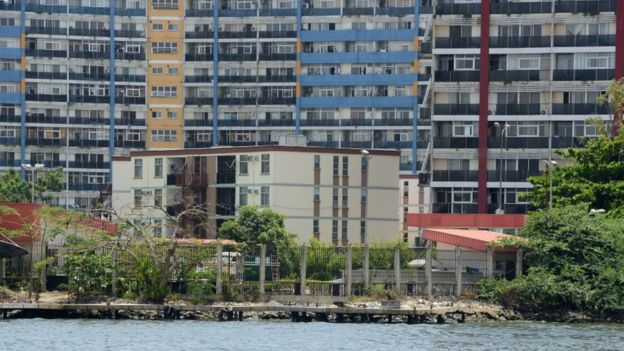

There is a shortage of small apartments preferred by young renters

One explanation for the expensive rent is that the cost of both land and construction is high in Lagos.

Also, there is a shortage of the type of small properties that people starting off in the rental market tend to prefer.

A new way of renting

The system of upfront payments suits landlords, but some innovations could start to help renters.

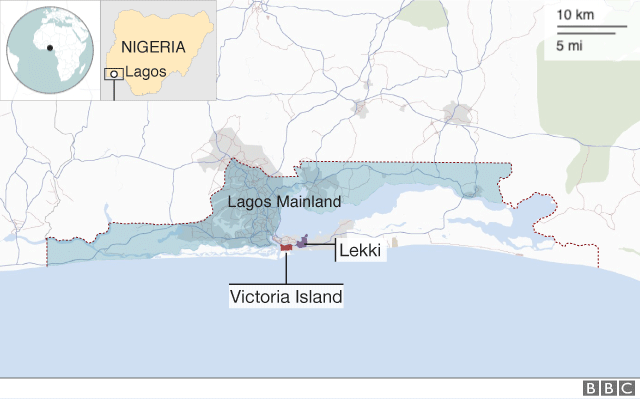

Bankole Oluwafemi, a young technology entrepreneur, has managed to secure a loft-style apartment on a serene residential street in Lekki – a fairly affluent neighbourhood. It is a step up from a house he shared with other young professionals.

Some people use informal lending networks to get the money – from parents, or saving while staying with relatives, and some firms offer their employees loans.

But Mr Oluwafemi managed to afford the place with the help of a digital rental site called Fibre.

The online platform allows users to rent properties with just a few clicks.

Tenants are given the option of paying monthly or quarterly, which may not seem extraordinary in many parts of the world, but is a potential market-changer here.

After Mr Oluwafemi finished his university degree, he moved to Lagos in 2011, but he was unable to come up with the two years’ rent in advance that landlords at that time were allowed to demand.

Unable to find an affordable apartment in a habitable condition, he slept on the floor of a room with 10 other people.

When he later co-founded a technology company, he decided to sleep in his office to avoid renting a home and the associated costs.

‘We take nothing for granted’

“Living in Lagos requires you to not just be a tenant, but in many respects you’re your own local government providing your own infrastructure,” Mr Oluwafemi explains, laughing.

He is referring to the fact that in addition to the cost of rent, many tenants are also expected to pay for their water and electricity, which can be difficult to organise and costly because of the fuel needed for generators.

“Fibre didn’t just come with the ability to pay monthly and the flexibility, these apartments come with a minimum standard of quality.

“People take these things for granted anywhere else in the world, but we live in Nigeria.”

Although the Nigerian government introduced legislation in 2011 limiting landlords’ rights to demand or receive more than one year’s rent from prospective tenants, it has proven difficult to enforce.

According to real estate analyst Dolapo Omidire, Lagos is largely a landlord’s market.

“They have the authority to dictate what they want from tenants,” he says.

“They can say: ‘These are my terms. If you don’t like it go somewhere else.'”

Long waiting list

Demi Ademuson and Obinna Okwodu co-founded Fibre three years ago and partner with landlords and developers to offer good-quality housing.

Driven by the desire to introduce some ease and flexibility to renting for tenants, the platform challenges a system they say that is inhospitable to young people.

“It provides a really high barrier for people just to access housing,” Mr Okwodu says.

“If you think about how fundamental housing is, it doesn’t make sense that for something so fundamental you have to jump through so many hoops.”

With 200 clients renting properties and 5,000 people on its waiting list, Fibre’s work represents a tiny fraction of the market, but it does offer an alternative way forward.

They also recognise that they started off at the high end of the market, but are beginning to broaden their prospective customer base.

The concept is working, but Mr Okwodu says it was initially a challenge to persuade landlords to accept monthly payments.

The company takes full financial responsibility if tenants default on payments – a vital element of the service that has helped to win clients’ trust.

Landlords like lump sum payments

However, many landlords have no interest in receiving payments in monthly instalments.

Deborah Nicol-Omeruah, a real estate developer in Lagos, can see how receiving monthly payments could work for property owners with mortgages, but she prefers the current system.

Some Lagosians with jobs on the island face a tortuous commute from the mainland

“A lump sum allows you to use the money for major expenses. For example, if you have school fees to pay or you have a big holiday that you want to pay for.”

Importantly, Ms Nicol-Omeruah says, 12 months’ rent in advance reduces the risk of default.

“When you have a client paying each month, there’s the hassle of chasing them for payments. If they’re a tenant with a high risk of default you might be chasing them monthly.

“With the current system there’s only one point each year that you have to chase your tenant for payment.”

Fibre’s success has inspired other entrepreneurs to launch similar platforms, but they are still too small to make a major impact on the rental market.

Many people have no option but to share a room, or stay with relatives.

‘Eight-hour commute’

Television presenter Uche Okoronkwo stayed with an uncle in a suburb on the mainland when she first moved to Lagos.

However, her eight-hour daily commute from home to and from her job on the island – where many companies are based – was punishing.

“Commuting between the mainland and island is hell. I woke up at four in the morning to get on an Okada [motorbike taxi] to line up for a bus by 04:30 to arrive at work at eight.

“Then I would get home at 10 or 11 at night because if you don’t leave the island before four you’re stuck in traffic. It made no sense to continue doing that. There was no quality of life.”

Ms Okoronkwo decided to move to the island, but because of a lack of affordable property, she rented a space known as a “boys’ quarters” or “BQ” – a small building within a compound containing a room and bathroom, which is traditionally used as a place for domestic staff.

“It was small and terrible,” she says. “The plumbing wasn’t good. There was no source of water. I had to buy a [water] tank and have it filled every month and then you relied on a generator for electricity.”

The high cost of land and construction is passed on to renters in Lagos

The real estate sector lacks quality control, according to industry analyst Mr Omidire, who has noted only a few developers are willing to invest the amount required to ensure a high standard of construction is met.

Despite this, he is excited to see a growing number of developers constructing one and two-bedroom apartments for young professionals.

He says this will address the imbalance between what consumers are demanding and the supply on the market.

Moreover, as more companies similar to Fibre launch in Nigeria, they are gradually breaking down the barriers to rent.

These online platforms are currently operating on a small scale, but as they grow they have the potential to disrupt the rental market, providing a smoother path to accessing property.