“I don’t know what Covid-19 is. All I can say is that it has come to disrupt our lives. I would have had my surgery by now if it were not for Covid-19. I don’t even know when the surgery would be possible. I am old, weak and my time is up. I am just waiting for God to call me.”

This is the woeful cry of 79-year old Avongo Kwonu who lives in Pungu in the Kasena-Nankana Municipality of the Upper East Region of Ghana.

For the last four decades, Avongo has lived with obstetric fistula, an injury which occurred when she was delivering her seventh and only surviving child.

During the difficult and prolonged obstructed labour which she endured without the support of timely medical treatment, Avongo started leaking urine, faeces and sometimes both. She has suffered from depression, and as she grew older, she has continued to sink into deepening poverty.

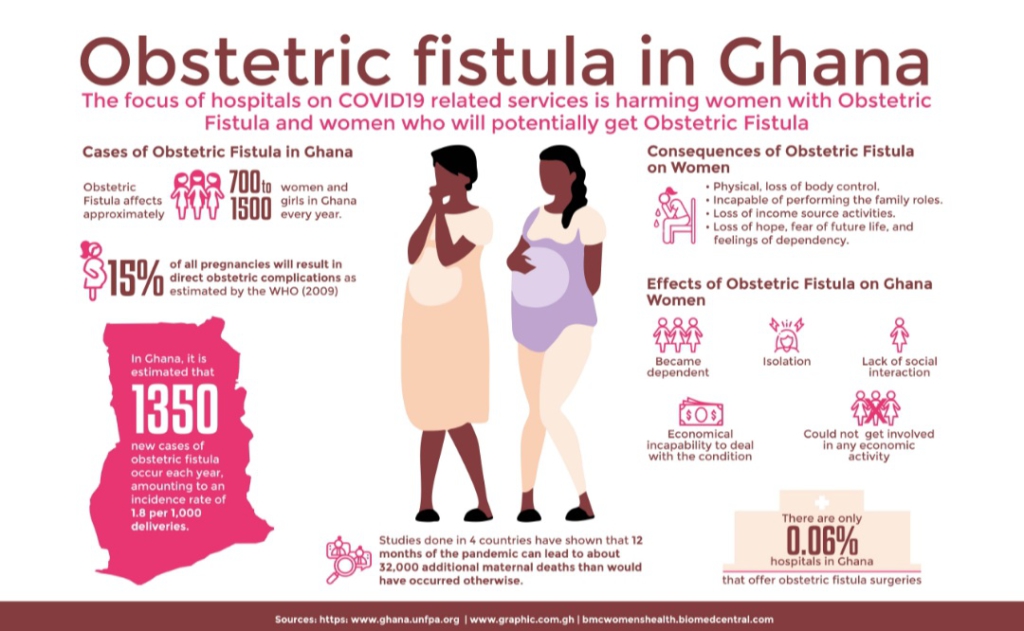

Every year, between 50,000 to 100,000 women worldwide are affected by obstetric fistula. The World Health Organisation estimates that more than 2 million young women live with untreated obstetric fistula in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Obstetric fistula is also a major cause of maternal deaths.

The magnitude of Obstetric fistula in Ghana is unknown and out of all the health facilities that provide delivery services, only six per cent provide treatment and repair of fistula, that’s according to a 2015 Ghana Health Service Report on the incidence of Obstetric fistula in Ghana.

Also, the same study carried out by the Ghana Health Service (GHS) in 2015, estimated that about 1,300 new cases of fistula occurred every year in Ghana and yet, not more than 100 cases are repaired each year leaving 1,200 cases without care. According to the report, the incidence of obstetric fistula in Ghana is estimated at 1.8 per 1000 deliveries.

A buoyant Avongo was looking forward to March this year as she was scheduled to under the surgery to repair the fistula injury. But Covid-19 happened. The government instituted lockdown measures and suspended all but necessary surgeries as it mobilised health facilities and personnel to address the Covid-19 virus.

Elective surgeries like the one Avongo has been waiting for most of her adult life were suspended. Elective surgeries are those that are not a medical emergency. The repair of fistula falls under the category of elective surgery. For women like Avongo, the decision by the government to suspend their surgeries is both a health and a human rights issue.

Avongo and other women like her have been left in limbo—they do not know when the surgeries they have been waiting for most of their lives will happen. She sees no end to the life of ostracism, stigma and neglect that has shadowed her for the last 40 years.

84-year old Afarabadaga Atiru is a widow who lives in Pungu in the Upper East Region of Ghana. Afarabadaga also curses the day Covid-19 emerged. “I am very annoyed because of Covid-19. Anytime I hear it being discussed on the radio, I get up and leave. What kind of sickness is this, with no cure at all? It just came to destroy us. Now, because of Corona they say that doctors cannot come and operate on us!” she fumesl.

She lost all her five children at childbirth and developed the fistula during her last birth. Abandoned years ago, by her family and her only surviving sibling, a sister, Afarabadaga ekes out a living farming. She is not able to produce enough to feed herself and depends on neighbours who sometimes give her food.

“My husband and I sometimes buy diapers for her and regularly visit to check on her,” said Doris Fankey, one of Afarabadaga’s neighbours.

Afarabadaga sleeps in a small room built for her by a good Samaritan. Her bed is the bare floor or bare wooden bench after her sleeping mat became tattered. Afarabadaga has never owned a mattress.

Isolated, ostracized by her community, Afarabadaga who does everything on her own, from cooking to washing her clothes, was looking forward to the surgery because it would have enabled her to finally rejoin her family. She hoped that she would not have to spend her last years on her own. “I do not want to die alone,” she says.

According to the Ghana Health Service, even though this condition prevails in all the regions of Ghana, the Northern Region has the highest prevalence.

At Kpandai in the Northern region, Niwuluga Balinbie who is in her 50’s talks of the number of times she has attempted suicide to bring an end to her suffering.

For the last 20 years, Niwuluga has suffered from constant incontinence, shame, social segregation. The worst is the rejection from her own grandchildren who refuse to eat her food during the rare times they visit her. “I have tried all sorts of medications for my condition.

They have all not worked. Whenever l go out in public, people avoid me because of the foul smell. When l cook, my grandchildren do not want to eat the food. I have prayed fervently to God to lift me out of this situation. I am tired. It is better to die than continuing living like this,” she says.

Niwuluga was scheduled to undergo fistula surgery this year. She underwent pre-surgery screening in December last year and was scheduled for surgery in March. “When I was taken to Tamale for assessment, I felt my prayers had finally been answered. Covid happened and now l cannot have the surgery!” says Niwuluga.

She is still optimistic and since the suspension, has been regularly asking her son to call the nurse of the Tamale hospital to find out when the suspension will be lifted.

“I want to know when doctors will be ready for us. The nurse always tells us that because of the virus, the surgery has been suspended.”

The operation can repair the physical injury but the emotional and mental suffering of women with fistula also impacts on their families and children. Women with fistula cannot engage in gainful employment which requires strict hygiene.

Niwuluga’s last son, Joseph, dropped out of school as his mother was no longer able to pay his fees. It was while giving birth to him that Niwuluga developed a fistula. Joseph lives with the guilt of being the cause of his mother’s condition and the taunts he gets from the community.

“In primary school, my peers used to say my mum is a witch because of her condition so they would shun my company. Some also mock me and accuse me of being the cause of my mother’s condition. I dropped out of school because of poverty. But the mockery has remained,” he says.

Joseph works as a laborer to support himself and his mother. But there are days he makes no money andresorts to begging from the neighbours despite their insults and taunts.

“My mother is always crying. My one wish is to see her undergo the operation. Once she is well, l can work towards achieving my dream of becoming a teacher,” says Joseph.

Rahinatu Issahaku is a Senior Nursing Officer at the Buya Health Centre in the Kpandai District. She has been mobilizing women for fistula surgeries for more than 10 years.

In December 2019, she was able to facilitate the transportation of Niwuluga and other fistula patients in the Kpandai District for assessment at the Tamale Teaching Hospital in the Northern Region of Ghana.

“The last time I sent them was in December 2019 when some doctors from the Czech Republic came to conduct some free fistula surgeries in Tamale. They were assessed and scheduled to be operated on after the new year, so I was preparing them to come for the surgery only for this Corona to pop in. I personally visit them to reassure them and also to get them some diapers and detergents.”

Rahinatu says she is inundated with calls from these women who want to know when they would also have their healing just like other repaired women.

In the Greater Accra Region, 27-year -old Mansa, (name changed to protect her privacy) has to deal with bringing up two babies on her own after their fathers abandoned her because of the fistula. She too was scheduled to undergo the surgery in March.

Mansa mistakenly attributes her condition to evil ‘spirits’.

“This problem is caused by the devil. During my second pregnancy, I had a nightmare that a man was chasing me with a cutlass saying he would operate on me but I refused. We fought in the dream. After I gave birth to the child, I once dreamt I was walking in the cemetery. Sometimes too, when I go to these ‘spiritual’ churches, the Pastors tell me that the target is to kill the child or me. Even when I was pregnant, they used to tell me that I would undergo surgery and could die as a result or lose my child. They also told me my enemies struck me with this condition in order to destroy my destiny.”

Obstetric fistula has stripped her of her dignity as a woman. She suffers from depression and has attempted suicide three times.

“I don’t feel worthy to be a woman. I cry whenever I think about my situation. It is better to die. I’ve tried to commit suicide three times but always failed. I think the reason it has not been successful is that God does not want me to die now.”

So far, she has managed to hide her condition from her boyfriend who supports her.

“Sometimes when my boyfriend asks me to visit, I don’t go that very day. I wait for about two or three days before going and during that period, I avoid drinking water. Eventually, the day I visit him, l avoid drinking water so that l do not soil myself in his presence. I am afraid that he will leave me once he knows about my condition,” she says.

She and other women have devised different methods of managing their incontinence from taking frequent baths, using strips of old clothes as pads, wearing extra clothes as cover, decreasing water intake and fluids.They also use scented soap for washing and spray perfumes whenever they afford it.

The prevalence of the obstetric fistula highlights the inequities that women and girls encounter in accessing reproductive health care, spotlights the economic and geographic barriers, the general weaknesses in the health delivery system and the social and cultural inequities that accompany the phenomenon.

To cater for the costs of the repair surgeries, a special fund, the Obstetric Fistula Fund was set up in 2018 at Access Bank to assist women and girls in need of medical treatment. Since then, a few individuals and organizations have contributed to the fund.

Obstetrician gynaecologist and fistula surgeon at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Dr. Gabriel Ganyaglo is a member of the fistula task force team.

According to him, the task force team carried out its last outreach in March at the Bole District Hospital.

“A very important thing to note is that the anesthesia part of the fistula repairs. Our Anaesthetists form the core of what we call the critical care teams in the Covid Centres. The few we have are in Covid care centres or in Covid teams. Yes, we are constrained in numbers and therefore it is better to deploy our human resource where the need is most critical.

“This has been the biggest impact of Covid on fistula repairs. This year in January, we were in Mankessim and we did a number of cases there, I followed up to Sabooba we did about 8 cases there, I moved to Bole where I did some fistula repairs.

“I got back from Bole on the 12th of March and on the 15th of March, the lockdown was in effect and it lasted for three weeks. From March till date, we haven’t had any outreach. I am aware of pockets of fistula cases in various locations and several colleagues in other hospitals have also called me about fistula repairs but on deliberating on the situation, as we have it today, we are not in normal times,” he revealed.

Although the lockdown lasted for only three weeks, Dr Ganyaglo says the team is yet to resume the surgeries. “These are not normal times,” he says.

He said the biggest concern was to avoid exposing those scheduled for fistula surgery to the novel coronavirus.

“I think for every patient, their priority is to avoid Covid-19 infection. From my interactions with the women, they are equally concerned about getting infected with the virus. If we assure them that it is safe to come, they will come. They know they are leaking; they have adjusted to life with leakage, they know they are stigmatized. They have adjusted to life with stigma so our effort is literally mostly to make them confident again, bring some quality to their lifestyle and that they want and would wish to have it as soon as it is safe to do that.”

Dr. Ganyaglo also admits the Covid-19 pandemic has affected general healthcare delivery at the facility including family planning services.

At Mercy Women’s Catholic Hospital in Mankessim, the Central Region of Ghana, the Medical Director,Dr. Justice Osei said the hospital carried out 80 surgeries in 2019. The operations were done with the support of Access Bank, Ghana’s First Lady Rebecca Akufo-Addo and other philanthropists.

Abena Manyamawu,one of the beneficiaries from Immuna in the Central Region said;“My situation is better now. In fact, God has been good to me.” She has been able to integrate into the community where she had previously been shunned because of her condition.

Dr. Osei said over 40 fistula patients were on the hospital’s waiting list. He cites the Covid-19 virus as a reason for postponing the surgeries. But he also admits that the hospital has yet to get any funding for the operations.

“We received a lot of pledges but we have yet to receive the money,’ he said.

He said the hospital decided to convert the fistula recovery ward into an isolation unit to cater for suspected Covid-19 cases.

“The fistula unit is there and it was a very difficult decision for us to take. It is currently because we are not having funding to carry out the surgeries that’s why one or two patients that we suspect have Covid have been admitted there,” he explained.

Dr Barnabas Naa Gandau, an Obstetrician Gynaecologist and Fistula Surgeon at the Tamale Teaching Hospital in the Northern Region said a medical team sponsored by the Women in Law and Development in Africa (WILDAF) was scheduled to carry out surgeries on an estimated 60 women who had been screened and assessed last year.

“There was a team that had been planning to come and do mass surgery led by WILDAF so we had the enthusiasm that by end of last year 2019, we would have had all cases operated on in the first quarter or latest in the second quarter of 2020. Unfortunately, as we were putting the place in order Covid-19 happened and we had to put everything on hold,” he said.

The WILDAF Governance and Health Ghana programme Esenam Ahiadorme said doctors from Spain were also to be involved in the surgeries. The doctors are sponsored by the African Women Foundation from Spain.

“We are doing it in collaboration with UNFPA and Tamale Teaching Hospital to help women with Fistula to do the surgery for them and also create awareness on the situation. As we speak there has been a hold on it because of Covid. The whole idea is that there was supposed to be experts from Spain to meet Dr. Gandau and the other experts in the Northern Region to come together as a team to do the surgery for at least 100 women. Unfortunately, they themselves have been badly hit by the pandemic in Spain,” she said.

Despite the delay, she is confident that the funding would not be withdrawn or re-directed. “We have received their confirmation that they will not withdraw the funding for these operations until at least the end of the year but we are still talking to them to extend their support in case things do not go back to normal by then,” she said.

She said her organisation did not have many resources at hand to provide support to the women with fistula and especially provide them with sanitary pads and diapers.

“It has been difficult. You go to certain offices, and when you mention fistula, the first thing they say is, we are talking about Covid and you people are still talking about fistula and it breaks your heart because people are not linking the challenge, they are facing in the midst of Covid. The virus has stopped everything! Now, everybody’s focus is on Covid.”

The fistula ward at Tamale Central Hospital in the Northern region which has been carrying out repair surgeries since 2009 was converted into a Covid19 isolation and treatment ward. Unlike other hospitals, the Yendi Municipal Hospital fistula unit which serves 10 districts does not do any outreach for fistula operations. Instead, the hospital relies on referrals and walk-in.

“We operate on a different system. We don’t do backlog clearance because we don’t go to do the patient recruitment. As and when they come in, we operate. We take care of patients from about 8 to 10 districts. Last year, we operated on 30 women and girls. This year, January we did not do a case, since the Covid, we’ve done two cases,” the hospital’s medical director and fistula surgeon Dr Ayuba Abdulai, Obstetrician Gynaecologist and a fistula surgeon explained.

Avongo Kwonu, Afarabadaga Atiru, Mansa and other fistula patients dotted across the country have once again had their lives put on hold. As Mansa put its— “it’s as if the virus purposely came for her.”

But there is hope for Mansa now as her prayer has been answered.She was part of the 10 fistula patients who had their surgeries at Mankessim in the latter part of August. For Mansa, the call from the nurse at the facility should have ended her woes but it did not.

“The day I was called to come and have the surgery, I got excited but at the same time I became sad because I had no money for transportation to the hospital. I had to borrow from a relative to be able to travel to Mankessim,” she said.

Weeks after the surgery, Mansa says, “I am doing fine by the grace of God. I am able to urinate with ease.” Among the over 40 patients on the hospital’s waiting list, Mansa is fortunate to be part of the few who were selected by the medical team to undergo the surgery.

“The funding has been a very big challenge for us. We had some organisations coming to help us for these surgeries. Tema Club paid for the repair of 10 patients,” Medical Director at the Mercy Women’s Hospital, Dr. Justice Osei explaining how Mansa and the other beneficiaries had their surgeries.

Apart from funding challenge, Dr. Osei admits that this selection was done to give an opportunity to those who have never undergone fistula surgeries.

“What this time around we decided to do was to operate on mainly those who have not had the surgeries before like the new cases. We still have quite a number of patients on the waiting list,” he said.

For the other fistula patients on the waiting list, their fate no longer hangs on Covid-19 and the restrictions placed on some surgeries but the benevolence of individuals and organisations to fund the processes for their surgeries.

“We have encouraged them not to give up, assured them that the next time we have funds, we will call them to come and have their surgeries,” these reassuring words from Dr. Osei are all they can bank their hopes on.

And for Mansa and the rest who have had their surgeries and recuperating, another hurdle lies ahead of them; getting on with life after surgery.

“I am fine by the grace of God. I am able to urinate with ease. For now, I would love to learn how to sew and also start a trade, so I’m appealing for support to get back on my feet,” Mansa said.

To address this myriad of challenges, Dr. Osei believes tackling the issue holistically is the surest way to mitigate the plight of these women.

“For me, we will continue to engage government and parliamentary select committee on Gender and Social Protection so that we will be able to have a holistic approach to managing such patients. The cost elements of fistula surgery and post- surgery should be incorporated into their annual budget so that there will always be funding to carry out fistula activities”, he stated.

For him, the existence of this medical condition is in itself a human rights concern.” I see Obstetric fistula as a human right issue. No woman should go through childbirth and come out with that complication and continue to live with it. Just as we have Free SHS and others, if we also take it upon ourselves and decide that we will dedicate a small budget for women with this condition without them paying anything, I think it would go a long way to lessen the burden on those of us taking care of these women and most especially on the women themselves.”

The impact of Covid-19 on our healthcare system cannot be underestimated, and as Dr. Osei put it; “Now Covid-19 has become part of our healthcare delivery so we have to integrate it into our healthcare delivery and make sure that we follow all the necessary preventive measures.”

That notwithstanding, women living with the condition who sometimes battle suicidal thoughts need to be given psychological support while they wait for their turn to undergo the surgery but this seems impossible because they are mostly unnoticed. This is because they have no support groups like other conditions such as HIV, Diabetes among others.

As Ghana hopes for and prays for a vaccine to be developed soon, the plight of Afarabadaga, Avongo, Niwuluga and other women still living with Obstetric fistula should not be relegated to the backgroundas preventing and managing this devastating medical condition contribute to the attainment of Sustainable Development Goal 3 of improving maternal health.

*****

The writer Beryl Ernestina Richter is a fellow of the African Women Journalism Project. This report is supported by the Africa Women Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ).