In October 2014, Nigeria received universal praise for its swift and efficient tackling of the Ebola pandemic which had struck West African neighbours Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia.

But the core team of staff from the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) who led the effort have since quit their jobs, because their salaries had not been paid for nearly three years.

“If they play back the clock, they won’t get me to do that job again,” says Dr Kenneth Madiebo, the 53-year-old medic who dealt with the body of Patrick Sawyer, the first identified Ebola case Nigeria in 2014.

A project officer with the NCDC since September 2012, Dr Madiebo was assigned the task of decontaminating the hospital room where Mr Sawyer had died in July 2014, and preparing his body for cremation.

In a video he showed me, Dr Madiebo, the only health official involved in the process, dons his protective gear and enters with a team of morticians to remove Mr Sawyer’s naked body from the narrow toilet where he had died.

Photo: Dr Madiebo, pictured next to the coffin, and a team of morticians worked together to remove the body of Patrick Sawyer

Photo: Dr Madiebo, pictured next to the coffin, and a team of morticians worked together to remove the body of Patrick Sawyer

Mr Sawyer had been certified dead at 7:30 but the removal of his body took place at 23:30 that night.

“Everybody was afraid,” said Dr Madiebo. “Nobody else wanted to do it. But I did it because it was my job.”

“I was ill for days afterwards but it was more psychological, not Ebola.”

Public praise came his way when Nigeria was officially declared Ebola-free on October 20, and the then Health Minister Onyebuchi Chukwu asked Dr Madiebo to stand up during a press conference and commended him openly for his key role in containing the virus.

That same month, the minister resigned his position to pursue other interests, while Dr Madiebo was promoted from project officer to incident manager, a position that came with a salary increase.

But, he has never received the new salary, or any other salary since then.

His colleague Colette Isu-Ezumah, a 43-year-old public health worker who moved back to Nigeria from the US in 2011, shares these frustrations.

She was a driving force behind the 250-strong group of Nigerian volunteers sent to Sierra Leone and Liberia for six months to help in the fight against Ebola, when infection rates were at their peak in 2014 and 2015.

‘No right to email’

Despite this, and just like Dr Madiebo, Ms Isu-Ezumah has not been paid since October 2014.

“Our boss kept telling us not to worry, that we would eventually get paid,” she says.

The 2014 Ebola crisis:

– Most deadly Ebola outbreak in history

– More than 11,000 people killed – mostly in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea

– Other deaths recorded in Nigeria, Mali, US

– Started in Guinea in December 2013, declared over in January 2016

Tired of all the placations, Dr Madiebo decided to take matters into his own hands.

At the time, President Muhammadu Buhari had just been elected, and with no new health minister named, Permanent Secretary Linus Awute was in charge.

Dr Madiebo sent an email to Mr Awute, copying in his six colleagues who were also out of pocket for nine months’ pay.

“You have no such right to write me directly, knowing that you are under several layers of authorities in the Federal Ministry of Health,” came the reply from Mr Awute in July 2015.

“Where is such impunity and unsatisfactory conduct coming from?”

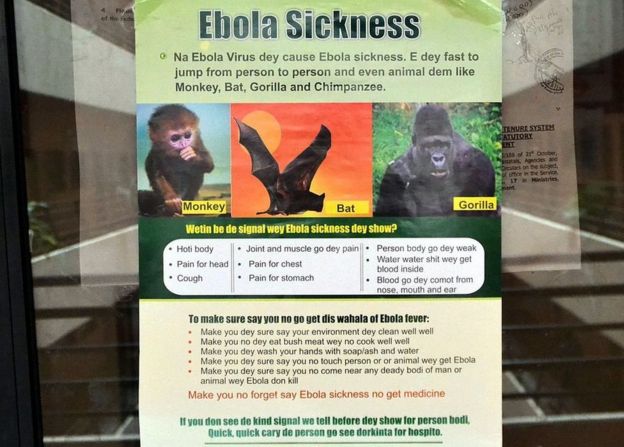

Photo: People of all ages, including schoolchildren, were advised to take precautions against Ebola

He added: “The terms of your engagement and payment of salary, to the best of my knowledge, was strictly under the Federal Ministry of Health/CDC Cooperative Agreement.

“Funding for your salary can only be accommodated under the Project and subject to availability of funding for which the CDC was unable to make further funding release to the Project.

The only mistake here is that Management of the Federal Ministry of Health ought to have disengaged you promptly to prevent this tendentious email.”

‘Show magnanimity’

But the final words in that verbose email from Mr Awute offered some hope:

“After my brief and the discussion that followed with the relevant Department, I went out of officialdom to abandon the nicety to show magnanimity by developing a plan to absorb you into the main stream Civil Service.”

Clinging to this glimmer of hope, Dr Madiebo and his colleagues kept on working.

Photo: Ebola warning signs are outlined on this poster in pidgin English in 2014

“I resigned my job in the UK to bring my 15 years of specialist training to help improve the deplorable health conditions in my country,” said Dr Chuks Ukpaka, one of the medical doctors who established the NCDC in September 2012.

“We were never disengaged but promised payment in arrears.”

Dr Madiebo’s next task was to co-ordinate a three-week monitoring period for those Nigerian Ebola volunteers on their return.

A more dangerous mission followed, when he took a blood sample from a suspected Lassa Fever patient in an Abuja hospital in 2016.

“Everybody thought I was crazy,” he says. “The lab staff were afraid to receive the sample from me.”

‘Desirous of justice’

Still, their salaries remained unpaid.

So Dr Madiebo kept writing to Mr Awute and other top health ministry officials, which he believes earned him a reputation as a troublemaker.

When the NCDC moved to a new building in 2015, Dr Madiebo says he was snubbed:

“I eventually stopped going to work because they refused to give me an office, so that they could justify not paying me.”

Nigeria has lost the expertise and experience of the team which fought Ebola

Abdul Nasidi, who was head of the NCDC from 2011 to 2016, confirmed that the salaries were not paid but says it was not his fault, adding: “Even I am owed salaries”.

Yet it appears Dr Madiebo’s email campaign is paying off, following an announcement in May 2017 from Nigeria’s current minister for health, Isaac Adewole, that a new committee is to investigate issue.

“The ministry is desirous of doing justice to these consultants,” says the man leading the committee and wider reforms at the ministry, Halad Keana.

He adds that the committee’s final meeting will take place in the first week of September, after which time a report and recommendations will be submitted to Mr Adewole.

In the meantime, Nigeria has lost the expertise and experience of the team which fought Ebola, and may have to start from scratch if faced with another deadly epidemic.

Photo: Drugs companies are trying to develop a vaccine against Ebola

Photo: Drugs companies are trying to develop a vaccine against Ebola

“I could not pay my rent, my children’s school fees, or my transportation to work,” Ms Isu-Ezumah says.

“When my son was admitted to hospital in March 2016 and I couldn’t pay his medical bill, I thought to myself: ‘If I were in the US, I would at least have insurance coverage'”.

She left Nigeria in July 2016, and now works for the US Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

Dr Ukpaka also returned to the UK, where he works as a trainer and a lead GP. But he says his heart is still in Nigeria and he is eager to return, despite feeling betrayed by his NCDC experience:

“There are so many challenges in the health sector there that require my services.”

Dr Madiebo still considers himself an NCDC employee because he has not yet received a dismissal letter, although he also plans to launch his own data and research company.

“They used me,” he says. “It would have been better for me to stay in my small cocoon, earn a small salary and not be involved in this.”