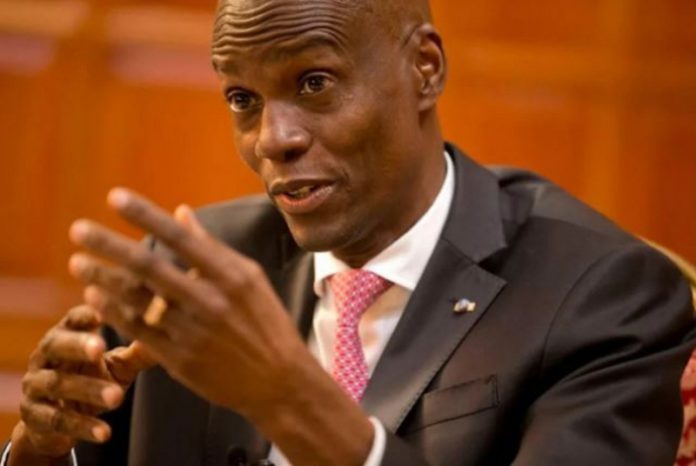

Today marks five years since Haitian President Jovenel Moïse came into office in an election that, instead of shoring up democracy in an already volatile Haiti, plunged it deeper into crisis and a bitter constitutional power dispute even before his July 7 assassination.

Marred by allegations of fraud and low turnout, the 2017 presidential vote took place 15 months after a disastrous first round that was discarded due to “massive irregularities.” Over the course of Moïse’s embattled Presidency and up to moment of his middle-of-the-night slaying, he faced mass protests, resignation calls and accusations of violating the constitution and illegally amassing power as he ruled by decree.

Now, on what should be the official end of Moïse’s presidential term according to the calculation of the U.S. State Department, Haiti will once again be without an elected president to swear in on Feb. 7.

The reality is setting off a possible confrontation and political standoff in the Caribbean nation. Senate President Joseph Lambert, stopping short of demanding that interim Prime Minister Ariel Henry step down, asked that he return the presidential sash to the Senate and requested that he refrain from engaging his “de-facto” government in any new business until “a broad consensus” can be reached between those promoting competing solutions as the way out of the crisis.

Unlike in 1990, 2004 and 2016, however, there is no Supreme Court justice or President to name as provisional head of state or Lower Chamber of Deputies and Senate to work out an agreement for an election.

With no functioning parliament or judiciary, and an interim prime minister who was named by Moïse but not installed until after the president’s death, Haitians are divided over how the transition should be structured, who should be in charge of it and what goals it should have.

The uncharted waters have many Haitians fearing chaos and more violence. Over the weekend there were reports of isolated incidents of violence in Port-au-Prince, and schools have told parents they will be closed on Monday. In a memo to police supervisors, the Haiti National Police announced that its 15,000-plus police force was to remain on high alert between Saturday until Thursday.

“We are currently in a state of political paralysis pregnant with uncertainty,” said Robert Fatton, author of “Haiti’s Predatory Republic: The Unending Transition to Democracy,” which analyzes the changing politics in Haiti from the demise of the Duvalier dictatorship through 2001.

The paralysis, however, is not sustainable, Fatton said, given the worsening security situation, deteriorating economic conditions and the ongoing struggle for power.

“A small incident or miscalculation could unleash a sudden and unpredictable political confrontation,” said Fatton, who teaches political science at the University of Virginia. “As the saying goes, the center does not hold and things are falling apart. In short, the crisis continues with no clear outcome.”

Last week during a U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee hearing, Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs Brian Nichols testified that the Biden administration is working with a cross-section of Haitian society “to encourage an inclusive solution to the political challenges that Haiti faces.” The U.S., he said, considered Henry to be one of the official representatives of the Haitian government.

Earlier this month, following talks between the U.S., Canada and several other Haiti allies, during which they called on Henry to redouble efforts to reach an inclusive political consensus on the path forward, Nichols said that from a legal standpoint, the term of the prime minister “is not linked to that of the term of the president.”

The international community, which would rather see elections in Haiti sooner than later, is worried that Feb. 7 could become a pretext for those seeking to challenge Henry’s fragile authority. Foreign diplomats know that as of Monday, Henry will face diminished legitimacy. At the same time, his relationship with a key suspect in the Moïse assassination who placed two calls to him on the morning of the killing, according to a Haitian police investigative report obtained by the Herald, has raised questions and served as ammunition for those seeking his exit from power.

Asked by Rep. Andy Levin, D-MI, during Thursday’s congressional hearing about U.S. support for Henry given the phone calls, Nichols said: “I have not received any information that Prime Minister Henry is culpable in the assassination.”

Henry has said he has no plans to step down and recently extended an invitation to different groups to send representatives to sit on a Provisional Electoral Council to begin planning elections. He currently has the support of several political parties that once protested against Moïse, and demanded his resignation. In recent days, he has tried to bolster that support by inviting others to sign on to his political accord laying out the plans for his transitional government.

Coups, crises and Haiti: Why this Caribbean diplomat is retiring after 45 years

Foreign governments have asked for Haitians to come up with a single agreement without specifying which accords should be merged. Last week, Haiti’s Catholic bishops joined the call, asking the competing political factions “to find the broadest possible consensus” in order for the country to return to full constitutional and democratic rule.

“The time is no longer for division, disunity, disagreement, discord, fratricidal struggles for power and the unbridled and shameless pursuit of selfish and petty personal interests,” the Episcopal Conference of Haiti said.

Depending on whom you ask, there are about a dozen political accords. While most, if not all, promote some sort of caretaker government to run the country, they differ on what the transition should look like and its duration. In addition to being tasked with staging the vote for the country’s elected leaders, some accords also push for a national dialogue and a new constitution. Some promote a two-headed government, while others call for just a prime minister.

But there appear to be three principal accords. One, the so-called Louisiana Unity Accord, emerged out of a summit last month involving several members of the Haitian diaspora. But the accord was called into question last week after Henry’s office announced a meeting with some of the proposal’s supporters.

The meeting came afer some of the accord’s original backers had pulled their support and as one accused a former lawmaker in Haiti’s parliament of trying to hijack the agreement.

The other two accords are one proposed by Henry, and one by the Commission for the Search of a Haitian Solution to the Crisis. Both have embarked on separate public relations campaigns to win over supporters, with the latter counting among its backers, Levin and other members of the U.S. Congress. The commission consists of civil society and human rights groups as well as others, and recently joined forces with a coalition of political parties, named PEN, founded by current and former political leaders.

Dubbed the Montana Accord because it was signed at the Montana Hotel in Petionville, the accord proposes a two-year transition. It would be led by a college of five presidents, which would come from different sectors of the society, including the current Henry government and the commission. A council of 44 people would oversee the presidential college as well as the prime minister who was selected in a vote by delegates last week. Also selected was the commission’s choice for provisional president to sit on the five-member counsel.

Economist Fritz Alphonse Jean, who was chosen by the Louisiana group as provisional president, was also chosen by supporters of the Montana/PEN Accord. Steven Benoit, a former presidential candidate and member of the Lower Chamber of Deputies, would be prime minister.

After moderate earthquakes kill two and injure dozens, Haiti seeks to educate public

Robert Maguire, a longtime Haiti observer and author of “Who Owns Haiti?” said it’s time for the international community to switch course.

Maguire believes that the supporters of the Montana/PEN Accord “merit the support and solidarity of all wishing to give Haiti a chance to achieve democracy that is more than simply hollow election exercises that are widely rejected by most Haitians. And that support and solidarity should include the international actors engaged in Haiti’s affairs, including the United States.”

Henry has thus far rejected the Montana /PEN Accord’s power-sharing offer, saying that the next occupant of the presidential palace will be elected. He has said he has no plans to step down Monday and he recently extended an invitation to different groups to send representatives to sit on the nine-member Provisional Electoral Council to begin planning elections.

In his September 11 Accord, which is named after the date it was signed, Henry proposes a prime minister but no president. The accord calls for the organization of new elections before the end of the year, and a new constitution.

If the Montana/PEN agreement has the potential of fueling more paralysis in a power sharing structure that has not worked well in Haiti at the municipal levels – mayors are part of a three-person group, which has been problematic in getting things done – then Henry’s accord is equally fragile. It is dependent on a coalition of political parties, which are already growing anxious about not being able to control key agencies, and on an international community increasingly under pressure to support a new leadership structure.

The Lambert letter to Henry requesting that he not engage the state in any new business could also become a hurdle.

A day before Lambert issued the letter on behalf of the Senate, the Montana/PEN Accord leaders also sent a letter. They have asked the senators and the Superior Council of the Judiciary to help find “a broad consensus” to exiting the crisis.

“Since the beginning of 2021, the executive has been operating in unconstitutionality, illegality and illegitimacy,” the signatories of the Montana/PEN Accord said in reference to Moïse, whose term, according to them, ended Feb. 7 last year. “In the face of the collapse of the state and the inability of the leaders of the executive to provide for the needs of our people … a multitude of sectors of civil society, grassroots organizations and political parties have agreed to seek a Haitian solution to the crisis.”

Fritz Pierre-Louis, a political science professor at CUNY Queens College in New York, said Haiti can’t continue on its current trajectory.

“If we don’t break this cycle Haiti will never get out of the situation that it’s now in,” he said.

Pierre-Louis said he doesn’t understand the international community’s support for Henry, or its call for Haitians to seek the broadest political consensus possible, which he believes will simply open the door to some of the same criminal elements and spoilers that have fed into the political dynamics that have put Haiti in its current situation.

“It’s hard for Haitians to get together, but the international community doesn’t encourage them to get together,” he said. He believes that the international community is missing the significance of Monday, Feb. 7. More than inauguration day, it’s a reminder of Haitians’ struggle for democracy, which has cost many lives over the decades.

“Feb. 7 was the birth of democracy for Haitians; they had high hopes of seeing change after 29 years of Duvalier,” said Pierre-Louis, 61, who has been involved in a number of democratic efforts and elections in Haiti over the years.

Regardless of what happens Monday, Maguire said Feb. 7 carries significance.

“That date now signifies that the great 1986 Haitian dream of democracy has been deferred for way too long,” he said. “Moïse did nothing to cease deferring it, as he dismantled and weakened public institutions, failed to organize elections as mandated in the constitution, and engaged in autocratic behavior – including relationships with violent gangs – meant to reinforce his power.”