The only hint that anything is wrong in La Estancia, a leafy suburb of the Mexican city of Guadalajara, are the dozens of “for sale” signs posted outside the houses.

People started leaving in May, when police found a decomposed body in a home on a quiet side street.

Last month, a kidnap victim escaped and directed police to another address on the same road. Inside, they found a corpse and three severed heads.

So far this year, more than 15 murder and burial sites – some holding dozens of dead bodies – have been found within homes in Guadalajara, the capital of Jalisco state.

‘You can feel the fear’

This is a frightening development in a country where more than 40,000 people have been reported missing since 2006.

Residents of Guadalajara are often too afraid to report suspicious activity to the police

When criminals bury victims in private properties, they create legal barriers to accessing their bodies. Search parties in Guadalajara can no longer rely on shovels. Instead, they now need diggers and drills to bore through concrete.

The silence of neighbours fuels impunity. Although some locals later reported hearing screams or smelling decaying flesh, few have dared to call the police.

“No one is reporting on what they know,” said one La Estancia resident who asked not to be named due to safety concerns. “You can feel the fear…it’s palpable.”

Since Mexico’s government deployed troops to fight drug cartels in 2006, mass graves have been uncovered with shocking frequency.

A study led by journalists Alejandra Guillén, Mago Torres and Marcela Turati found at least 1,978 clandestine burial sites were unearthed between 2006 and 2016.

Authorities have made little effort to locate these graves. Instead, politicians have routinely painted the disappeared as criminals, despite overwhelming evidence that there are many law-abiding civilians among them.

Digging for the dead

Across Mexico, desperate parents have taken up the task of digging for the remains of the missing. These informal investigations have led to shocking discoveries.

In 2016, an anonymous tip-off led one collective to a wooded area in the eastern state of Veracruz. At least 298 bodies and thousands of bone fragments were eventually recovered from the site.

But the obstacles to finding missing people in Guadalajara have multiplied in recent years, says Guadalupe Aguilar.

Guadalupe Aguilar has spent eight years looking for her son, José Luis

A founding member of Families United by Disappearances in Jalisco, Ms Aguilar has been searching for her son, José Luis Arana, since he disappeared in a Guadalajara suburb in 2011.

“In [other regions] criminals are closer to the countryside,” Ms Aguilar explains.

“Here in the city, it’s much riskier to transport a dead body… But it is always more difficult to search a private property because you need a warrant to enter.”

A city at war

A police official who spoke to the BBC under the condition of anonymity says two gangs are behind the burials in Guadalajara homes.

The first is the Jalisco New Generation cartel (CJNG), which the government considers the country’s most powerful criminal organisation.

The second is Nueva Plaza, a rival group which split from the CJNG in 2017, sparking violence across the city.

“[These gangs] rent from landlords who have no idea what the property is being used for,” the official said.

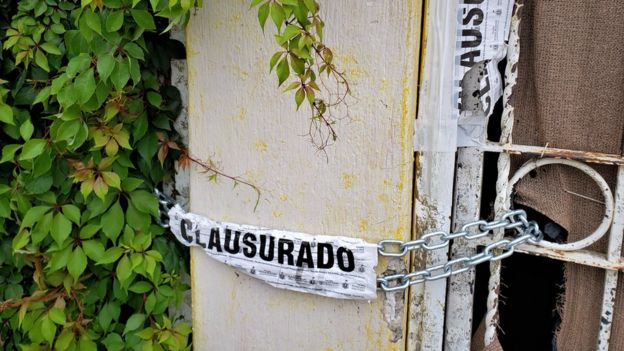

Homes, where bodies have been found, are cordoned off by officials

“We have also documented cases in which they simply invade. They find uninhabited properties and turn them into torture houses or burial sites.”

This strategy has not been seen on this scale in Mexico since 2011 – after a series of mass killings in the northern state of Durango.

But the police official warned the burial tactic could soon spread to other cities, as criminals from Jalisco, particularly the CJNG, strengthen their grip across the country.

Poor and underpopulated areas are particularly vulnerable to cartel invasions. The problem is so severe in Chulavista, a housing complex on the fringes of Guadalajara, that locals brick up the doors of abandoned homes to prevent criminals from seizing them.

‘No one is looking’

Jalisco’s security crisis made international news in September last year, when authorities parked a refrigerated trailer filled with 273 unidentified bodies in suburban Guadalajara.

Octavio Cotero’s daughter has been missing for over a year

The state government had rented the container after a surge in violence overburdened forensic facilities.

Politicians blamed the scandal on Jalisco’s forensic chief, Octavio Cotero. But Mr Cotero accused the state of ignoring his appeals for funding.

He also revealed there was a second trailer containing more unidentified bodies.

Both the Jalisco state government and the federal government changed following elections in July 2018.

But Mr Cotero says that the new leadership, which was sworn in in December, is not addressing the disappearance crisis.

According to Mr Cotero, the number of bodies found in burial pits in Guadalajara homes exceeds the official capacity to identify them. “We need to invest in [forensic] training,” he argues.

For the former forensic chief, Mexico’s security crisis is also a personal tragedy.

In July last year, his daughter, Indira Cotero, vanished without a trace. That month, police announced they were searching a Guadalajara property as part of the investigation. But Mr Cotero says nothing has been done since.

“The worst thing is not knowing where she is,” he said. “And the fact that nobody is looking.”

Source: BBC