As Ghana steps up its fight against climate change, much of the focus has been on flood control and drainage systems.

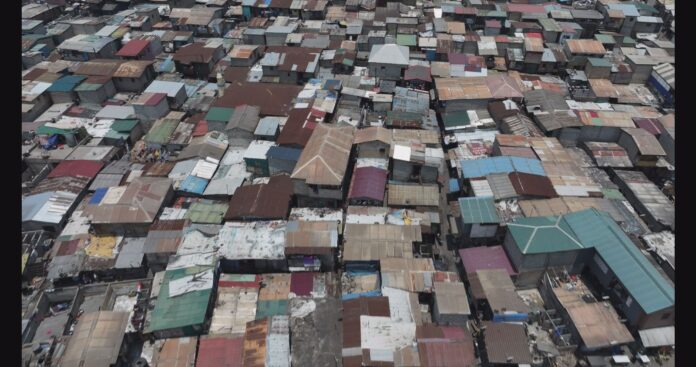

However, in Agbogbloshie, one of Accra’s most vulnerable urban communities, residents are confronting another silent but deadly threat: extreme urban heat, intensified by toxic pollution and overcrowded housing conditions.

While national initiatives like the Greater Accra Resilient and Integrated Development Project (GARID) aim to boost the city’s climate resilience, many argue that the poorest neighborhoods are being left behind.

Extreme Heat in Accra’s Slums: Life Inside an Urban Oven

In Agbogbloshie, heat is more than just uncomfortable—it’s life-threatening. Narrow alleys, metal roofs, and poor ventilation trap scorching temperatures, turning homes into ovens where conditions regularly exceed safe levels.

“My children have heat rashes every day. We pour water on the floor to cool the place, but it still feels like we’re suffocating,” said Madjin Wachichi, a yam seller.

Inusah Damata, a maize seller, added, “At night, the heat remains unbearable. We pay 80 cedis for this room, but it feels like living in fire.”

Public health experts warn that chronic exposure to extreme heat can lead to heat exhaustion, dehydration, and respiratory problems, particularly among children and the elderly.

Toxic Air, Burning Wires: The Hidden Health Risk of E-Waste

Agbogbloshie is notorious as one of West Africa’s largest e-waste recycling hubs. Daily, scrap dealers burn electrical wires to extract metals, releasing thick smoke loaded with hazardous chemicals.

“I know the smoke is dangerous. It makes my chest hurt, but this is how I survive,” said a scrap dealer.

Prof. Felix Hughes, a physicist at the University of Ghana, explained that burning e-waste exposes people to heavy metals such as lead, mercury, and cadmium.

“Inhaling fumes from burning e-waste introduces toxins into the lungs, causing long-term respiratory diseases and neurological damage,” Prof. Hughes said.

These toxic emissions, combined with extreme heat, create a dangerous mix that threatens both air quality and public health in Accra’s inner-city areas.

Scientific Evidence: A Heat-Health Time Bomb

Research by Dr. Ebenezer Amankwah, a geography lecturer at the University of Ghana, highlights a growing “heat-health burden” in informal settlements like Agbogbloshie.

The 2024 study found that indoor temperatures in slum areas can be up to 5°C higher than in other neighbourhoods.

“When you combine heat with poor housing and toxic environments, you create a public health time bomb. GARID’s interventions must reach these communities urgently,” Dr. Amankwah explained.

The study links these conditions to increased cases of heat-related illnesses, respiratory infections, and fatigue among residents, showing that climate inequality is intensifying in Accra’s low-income areas.

Government and EPA Efforts to Reduce Urban Heat

To tackle rising temperatures, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is promoting urban greening projects under the GARID initiative, planting trees, creating shaded areas, and reducing heat in densely populated communities.

“We want to reduce heat by increasing shade. Trees, not tiles, are key,” said EPA CEO Prof. Nana Ama Klutse.

However, Agbogbloshie has yet to benefit from these interventions. The few existing trees struggle to survive amid concrete, smoke, and overcrowding.

Residents have taken matters into their own hands, organising community clean-ups and heat awareness campaigns, but they stress that government support is essential to achieve lasting change.

Climate Inequality and the Fight for Survival

For the people of Agbogbloshie, climate change in Ghana is not just about rising seas or floods—it is about daily survival under extreme heat and toxic air.

Without urgent and inclusive action, urban neglect will continue to claim lives in Accra’s poorest communities.

“Climate resilience must be inclusive—no one left behind,” residents insist.

Source: Prince Owusu Asiedu

This story is in partnership with CDKN and the University of Ghana C3SS with funding from CLARE R4I Opportunities Fund.