Agooo!

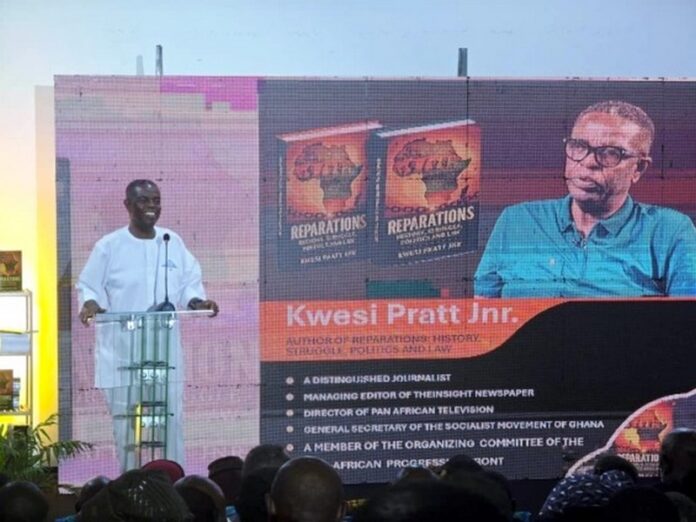

Comrade Kwesi Pratt Jnr. has delivered a powerful Pan-African clarion call for reparations. Reparations is a bold, unapologetic 152-page demand for reparative justice — not only for slavery but also for colonialism.

The strength of this book is evident in how much it influenced President Mahama’s 2025 UN address, a speech that was hailed across the African continent and diaspora.

My favorite chapters are Chapters 3 and 4. In Chapter 3, titled The Case for Reparations, Mr. Pratt writes, “On a moral level, it is pretty straightforward. The transatlantic slave trade led to the kidnapping and forced labour of over 12 million Africans, along with countless deaths.

After that, colonialism brought even more misery: taking land, forced labour, stealing resources, destroying cultures, and mass killings. These were not just mistakes; they were deliberate actions by governments and institutions looking to profit off African lives.”

Elsewhere, he observes, “Reparations are also about reshaping the story. They take history back from those who oppressed and give it back to those who were oppressed.”

Mr. Pratt supports his argument with strong historical precedents, including the billions paid by Germany to Israel and Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, by the United States to Japanese Americans, and by Western nations to indigenous populations. He notes that the African Union’s calls for reparations are grounded on these very precedents.

He transforms the call for reparations from a purely African demand into a global movement by citing the case of India, which lost an estimated USD 45 trillion to Britain between 1765 and 1938.

He insightfully identifies the debtors of reparations as “states, corporations, religious orders, and wealthy families whose fortunes are built on the backs of enslaved Africans, colonized people, and pillaged resources.”

Mr. Pratt also explores possible models of reparations — including cash payments, debt cancellation, and investment in infrastructure, technology, and education.

Particularly compelling is his call for the establishment of Pan-African universities to educate and empower the continent’s youth. He proposes that reparations should be both continental and diasporic, estimating the cost at $2 trillion in slave labour and between $4–6 trillion for colonial resource extraction.

However, I noted two major omissions and a few cautions in this otherwise commendable work.

First, the book overlooks the Arab slave trade, which lasted longer and may have extracted even more labour from Africa. Secondly, it does not adequately address the complicity of African interior empires and coastal elites who became indispensable partners of European slave traders. These elites transformed cities such as Anomabu, Cotonou, and Dakar into wealthy trading hubs that rivalled Liverpool, Charleston, and Savannah in their time.

Additionally, I am concerned about accountability for reparations funds. If some elites in Ghana could misappropriate Covid-19 relief funds, and Nigerian kleptocrats could loot recovered Abacha assets, who can guarantee that reparations funds would not suffer the same fate?

Despite these minor blemishes, Comrade Pratt has written a classic that deserves to stand beside Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost, Eduardo Galeano’s Open Veins of Latin America, and Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. It is a vital contribution to global justice and should be required reading for anyone who believes in moral restitution and historical truth.

In salute, I say, “Comrade Kwesi Pratt, Aluta Continua, Victoria e certa!”

Arthur Kobina Kennedy