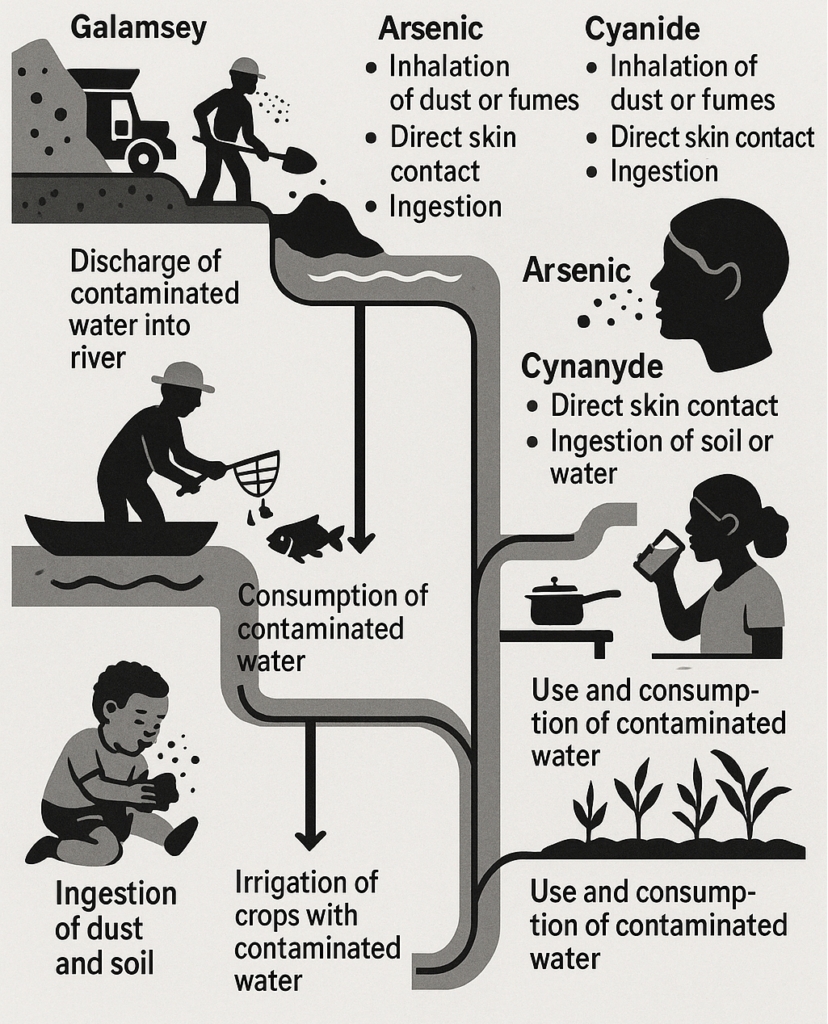

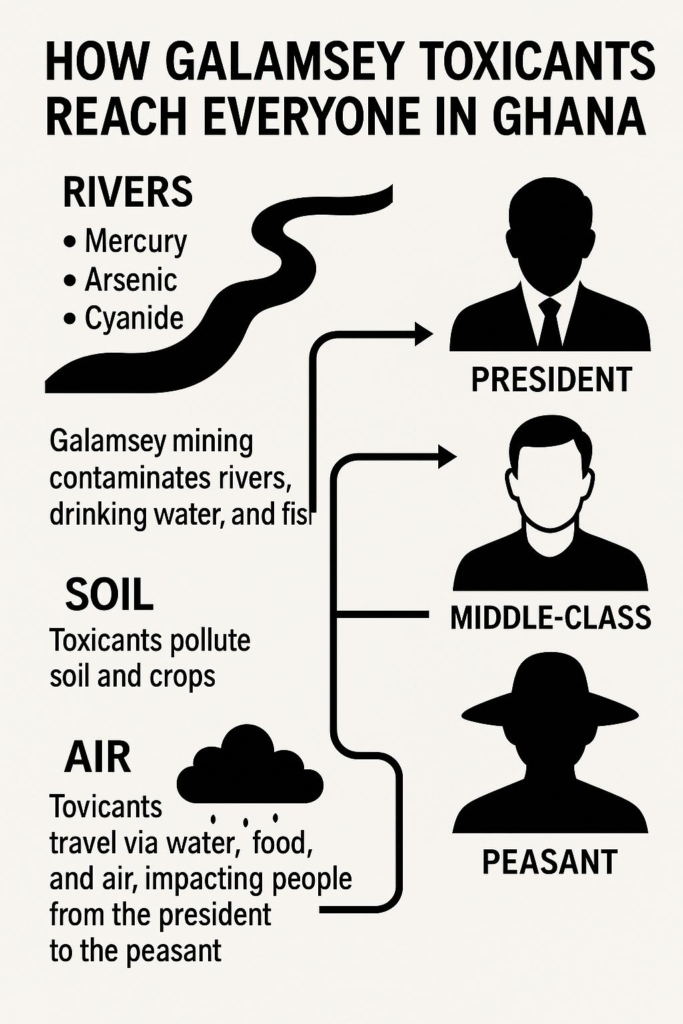

Once hailed as a “watered paradise,” Ghana’s lush forests and rivers are now soaked in poison. Illicit gold mining or galamsey has exploded across the country, leaving in its wake a toxic stew of mercury, arsenic and cyanide.

Today, these pollutants hitchhike on every river, soil particle, breath of air and morsel of food.

“That’s the river we used to swim in as kids,” recalls an environmental activist, gesturing at a nearby tributary now coffee-brown with mine waste.

“We used to drink from it and irrigate our farms. Now it’s poison.” Across Ghana, from remote villages to the capital’s dinner tables, no one is truly exempt from exposure to galamsey’s chemical legacy.

Rivers Run with Poison

Galamsey miners sluice and dredge Ghana’s rivers by the thousands. They pour liquid mercury into the muddy pans to bind tiny gold flecks; after the gold is skimmed off, the miners burn the mercury, releasing toxic vapor.

This volatile mercury travels far, raining down onto fields and water bodies even hundreds of miles away. In the Pra, Birim, Offin and other river basins, freshwater sources are now widely tainted by mining chemicals. Ghana’s water utility warns that if this contamination continues, the country may have to import drinking water by 2030.

In the rivers themselves, the evidence is plain. Tiny fish along the Pra have turned bright yellow or died off entirely, suffocated by toxic water.

Markets along the riverside now see water that is golden-brown from chemical runoff; villagers lament that every fish and maize plant has been killed by the contamination.

In lagoons and lakes, arsenic and mercury have been detected in fish at levels unsafe for human consumption. In other words, every catch poses a health risk, especially to children and pregnant women.

Cyanide, used by some miners to dissolve gold, is extremely toxic. Accidental spills and acid runoff have caused acute poisonings, killing fish and leaving villagers with severe stomach and skin ailments. In some places, entire tributaries have been acidified, with fish dying and their skins peeling from chemical burns.

Arsenic levels in historic gold belts have soared many times above safe drinking limits. Groundwater wells in mining zones likewise show contamination, meaning the problem is not confined to rivers but is seeping underground.

Toxic Soils and Wilted Crops

It’s not just water — the very earth is poisoned. Every mine site leaves behind tailings and dust loaded with heavy metals. When rains fall, these toxins run onto adjacent farms.

Fields once filled with cocoa have been devastated, stripped of fertility and turned into pits. Entire cocoa plantations have been destroyed by mining. Farmers report that when they irrigate with polluted water, every flower and pod drops off the cocoa trees.

Mercury vapor from processing settles on soil, while arsenic and cyanide seep underground. Plants absorb these hidden toxins. Cocoa, cassava, maize and vegetables irrigated with contaminated water accumulate metals, passing them into the national food supply. Farmers who once sold food now travel to towns to buy what they need, unable to sustain their farms.

Airborne Hazards

Mining also fills the air with dust and fumes. When mercury amalgams are burned, toxic vapors drift into the atmosphere and travel long distances before settling back onto land and water.

Roasting arsenic-bearing ores sends arsenic aerosols skyward. Dust from open pits spreads cadmium, lead and silica. These airborne particles fall with rain, washing toxins into rivers or onto farmland.

Communities far from mining sites report unusual crop failures and clusters of illnesses. Mercury and arsenic in the air provide one explanation, showing how even areas that appear untouched are, in reality, part of the contamination map.

On Every Plate and in Every Cup: Human Exposure

The toxic trail inevitably leads to people’s bodies by many routes. Drinking water is the most direct. In mining districts, villagers drink from rivers and wells often laced with chemicals. Even in cities, water reservoirs may draw from tainted watersheds.

Food is another pathway. Fish are particularly dangerous because they bioaccumulate mercury and arsenic.

From Lake Volta to coastal lagoons, the fish sold in markets often carry dangerous loads of these poisons. Vegetables and grains irrigated with contaminated water add another route of exposure.

Occupational exposure is the most extreme. Thousands of miners and their families live at mining sites, inhaling dust, handling liquid mercury with bare hands, and bathing in contaminated ponds. Pregnant women in these areas pass mercury, arsenic and cyanide directly to their unborn children. Babies are born with birth defects linked to chemical exposure.

Even the wealthy are not immune. Families in Accra and Kumasi may drink bottled water and eat imported food, but much of Ghana’s fish and farm produce enters urban markets. A family dinner in the city may still contain cocoa, cassava or tilapia grown or caught in contaminated zones.

Illness and Inequality

The human toll is devastating. Mercury causes tremors, vision loss, hearing impairment and brain damage, especially in children.

Arsenic is a potent carcinogen linked to cancers of the bladder, lungs, liver and skin. Cyanide can kill quickly in large doses and damage the thyroid and nervous system in smaller ones.

The poor are disproportionately hit. They rely on untreated water and local crops, bearing the brunt of exposure. Miners’ families live in the most toxic environments.

But wealth does not guarantee immunity; even the president may dine on food unknowingly tainted by galamsey’s chemical reach.

Systemic Neglect and Accountability

Legally, Ghana has a duty to protect its citizens’ right to a clean and healthy environment. Yet enforcement remains weak. Officials often turn a blind eye or are accused of complicity. Activists have faced intimidation and even death for speaking out.

Environmental laws exist on paper, requiring miners to obtain permits and treat waste. But illegal operators ignore them with impunity. Communities protest, demanding their right to live in a clean environment, but accountability is rare.

Across the country, citizens march with banners reading “Our soil bleeds mercury; our crops wither.” They demand justice and accountability, calling for polluters to be held liable and for systemic neglect to end.

A Nation at the Crossroads

The choice is stark. Mining without accountability has turned a blessing into a curse. Heavy-metal toxins persist in rivers, soils and human bodies for generations. Ghana’s poisoned water and farmland stand as a warning: without urgent action, every citizen, from the president to the peasant, will continue to bear the toxic toll of galamsey.

The writer is a lecturer at the Department of Food and Nutrition Education, Faculty of Health, Allied Sciences and Home Economics Education, University of Education, Winneba.

Source: Dr Ekpor Anyimah-Ackah