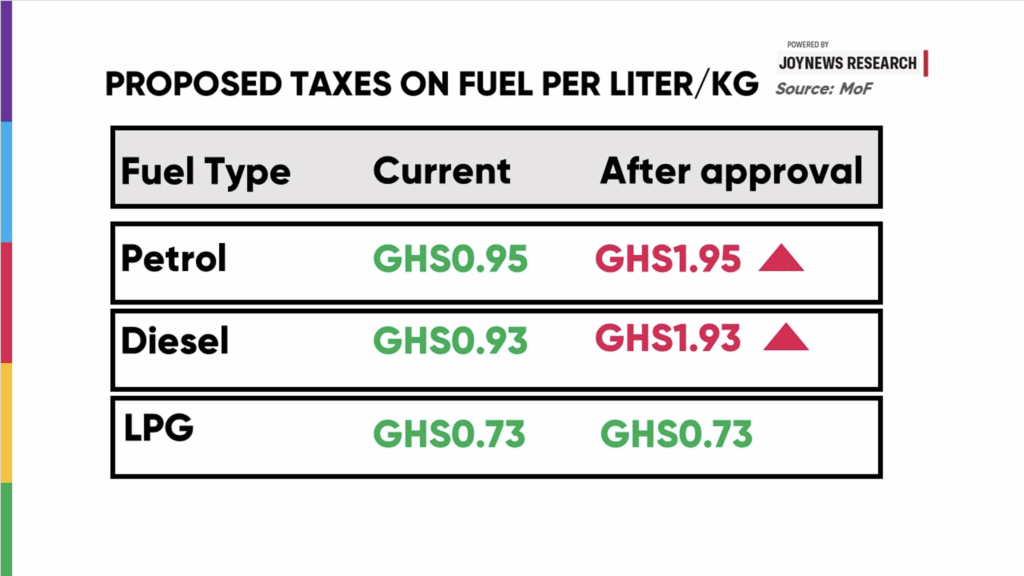

In the early hours of June 4th, 2025, Ghana’s Parliament approved a GH₵1 increase to the Energy Sector Shortfall and Debt Repayment Levy on petrol and diesel.

This amendment to the Energy Sector Levies Act (ESLA), pushed through under a certificate of urgency, raises the levy to GH₵1.95 per litre for petrol and GH₵1.93 for diesel.

Liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) was excluded.

The Energy Sector Levies Act, introduced in 2015 and implemented in 2016, was designed to streamline energy-related taxes and rescue struggling state-owned utilities.

According to the Ministry of Finance, total collections from all ESLA levies between January 2016 and December 2024 reached GH₵27.2 billion.

In 2025, the government expects to collect GH₵9.57 billion, and data obtained by JoyNews Research from the GRA shows GH₵2.1 billion has already been collected in the first five months of 2025.

This brings total collections to over GH₵29 billion.

So why is another GH₵1 being added to fuel prices, and where did all the previous billions go?

Unbudgeted, but Convenient

The tax hike didn’t appear in the 2025 budget.

In March, Finance Minister Dr. Cassiel Ato Forson explicitly assured Parliament that the levies would be reviewed, but not raised.

“Without increasing the levy, we will also review the Energy Sector Levies Act to consolidate the Energy Debt Recovery Levy, Energy Sector Recovery Levy (Delta Fund), and Sanitation & Pollution Levy into one…”

Less than three months later, the promise has been broken.

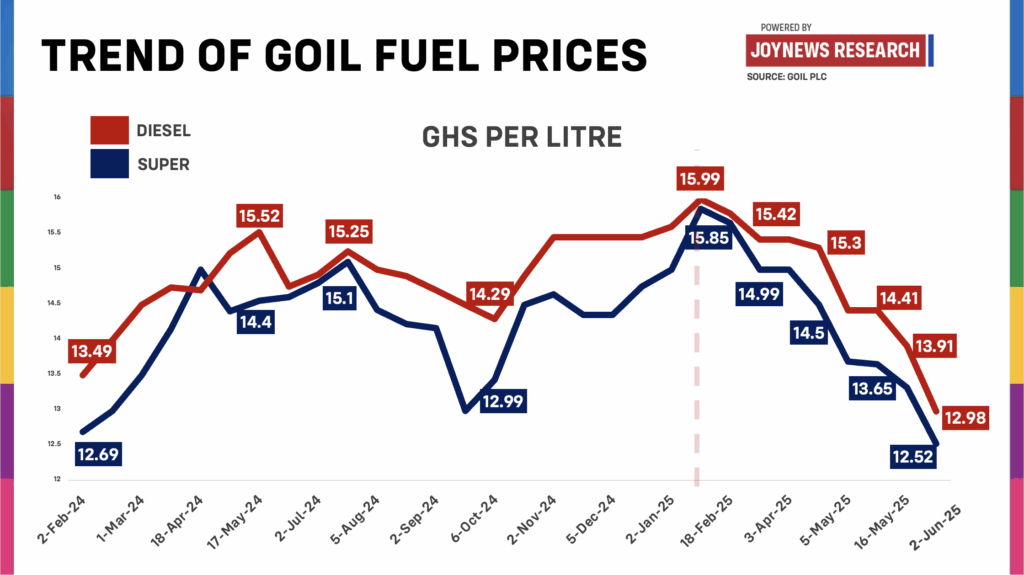

The reason? Falling global oil prices and a surging cedi have brought fuel prices to their lowest levels in over a year—giving the government cover to introduce the hike without triggering public outrage.

At GOIL stations, diesel is now GH₵12.98 per litre and petrol GH₵12.52, down from nearly GH₵16 earlier this year.

Some private marketers are even selling below GH₵12.

The Ministry of Finance believes this creates “fiscal space” for the new levy without causing significant consumer backlash. But with transport unions already cutting fares by 15 percent, it remains to be seen how drivers will react once the levy kicks in.

A Growing Shortfall

The government justifies the GH₵1 increase as necessary to support the widening energy sector shortfall and ensure stable power supply.

The sector’s deficit stood at $1.46 billion in 2024 and is projected to rise to $2.23 billion in 2025.

Total accumulated energy sector debt hit $3.1 billion by March this year.

A big part of the problem is Ghana’s reliance on expensive liquid fuels to power thermal plants. The country is expected to spend $1.2 billion on these fuels this year.

Since these costs fall outside regulated tariffs, they create a financial sinkhole—unless tariffs rise by as much as 50%, a move that would be politically unpalatable for any government, let alone a new one.

That raises questions.

Why Liquid Fuels?

Ghana has 15 thermal plants, most designed to run on natural gas. Eight can switch to liquid fuels when gas is unavailable. Given that natural gas is cheaper and more stable, why the shift to costlier alternatives?

Likely explanations include supply shortfalls from the Atuabo Gas Plant or disruptions along the West African Gas Pipeline (WAPCo).

If so, clearer public communication is needed.

Taxing instead of fixing?

Even the Finance Ministry admits the deeper problems are structural: poor revenue collection, system losses, weak enforcement of the Cash Waterfall Mechanism, and costly generation contracts. Add in underperforming utilities and misallocated subsidies, and the sector becomes a black hole for public funds.

Which begs the question: if these issues are known, why raise taxes instead of fixing the system?

Private sector involvement in electricity distribution by the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG) is being considered to plug these holes.

But if reforms succeed, will the GH₵1 levy be removed?

Or will it quietly become permanent, like so many “temporary” taxes before it?

Show Your Work

The government insists the new levy won’t hurt, because fuel is cheaper and the cedi is strong.

But if either trend reverses—if oil prices rise or the cedi slips—the tax could undo recent gains in consumer relief.

The motive of fiscal stability is sound. But Ghanaians deserve clarity: Why are liquid fuels being prioritized over gas? Is this a short-term fix or a long-term strategy? What’s the plan for reversing the tax once conditions improve?

Above all, transparency is essential.

Once implemented, the public deserves regular updates on how much has been raised, how it is being spent, and whether the tax is actually delivering results.

More importantly, If GH₵29 billion didn’t solve the problem, will one more cedi?