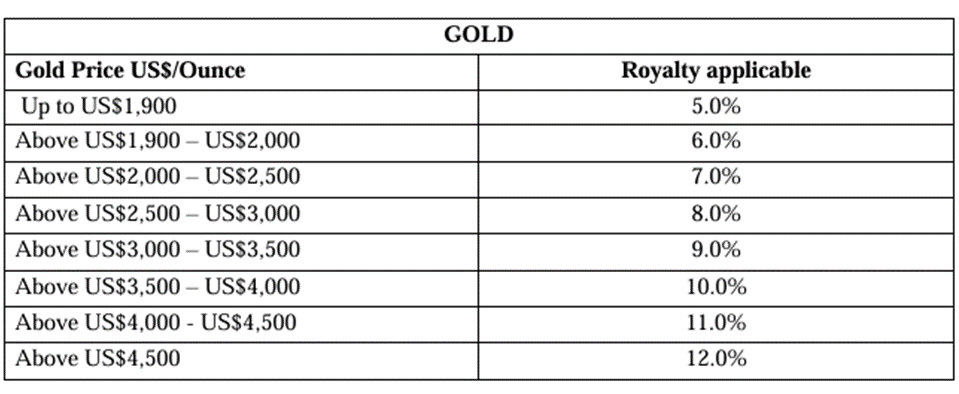

On Friday, December 19, 2025, the final sitting day before Parliament rose for the Christmas recess, the Minister for Lands and Natural Resources laid before Parliament a Legislative Instrument seeking to introduce a sliding scale royalty structure for all minerals in Ghana.

The move is mandated by the Minerals and Mining Amendment Act, Act 900 of 2015.

The sliding scale was initially expected to apply only to lithium, to enable the laying of the lithium mining lease between the Government of Ghana and Atlantic Lithium through its local subsidiary, Barari DV.

Instead, the ministry extended the framework to cover all minerals, with gold the most significant addition.

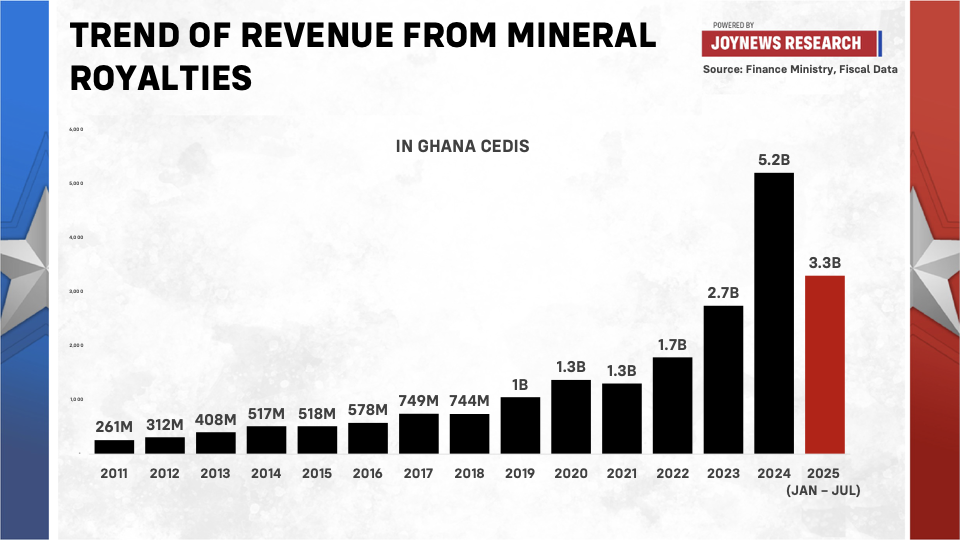

This matters because mineral royalties are a meaningful source of government revenue.

In 2024, the Finance Ministry reported GHS 5.2 billion in mineral royalties, excluding oil. Finance Ministry data also shows that from 2011 to the first seven months of 2025, Ghana received more than GHS 20 billion in mineral royalties alone.

Ghana’s current gold mining fiscal regime includes a general royalty rate of 5%, with three companies operating under development agreements that apply rates between 3% and 5% depending on gold prices.

Mining companies also pay a 35% corporate income tax, a 3% growth and sustainability levy, as well as other taxes such as import duties, withholding taxes, mineral rights fees, ground rent and Pay As You Earn (PAYE).

Of the 25 large scale mines in Ghana, 16 are members of the Ghana Chamber of Mines.

These 16 companies reportedly paid a combined GHS 17.6 billion to the government in 2024. Corporate income tax accounted for GHS 10.3 billion, making it the single largest contributor.

Out of Ghana’s total tax revenue of GHS 151 billion in 2024, contributions from the large scale mining sector accounted for about 11% of total government revenue.

Given this scale, the proposed sliding scale has potentially significant implications for both government revenue and investment in the sector.

After accounting for royalties, corporate income tax, ground rent and mineral rights fees, the Natural Resource Governance Institute estimates that Ghana’s effective tax rate on mining companies already exceeds a little over 50%.

In practical terms, this means the state captures more than half of mining company profits.

In October 2025, the Minerals Commission wrote to large scale mining companies notifying them of a comprehensive forensic audit of their books covering the previous ten years, to ensure regulatory and fiscal compliance.

Following that notification, there was no public update until the sliding scale was laid before Parliament.

This led to speculation that the audit may have uncovered weaknesses in the existing regime, prompting the move to increase royalty take.

However, despite repeated attempts to obtain confirmation from the Lands Ministry, no response has been provided on whether the audit has been conducted.

The Ghana Chamber of Mines, however, has confirmed that no audit has taken place yet.

It therefore cannot be concluded that evidence of fiscal leakages triggered the introduction of the sliding scale.

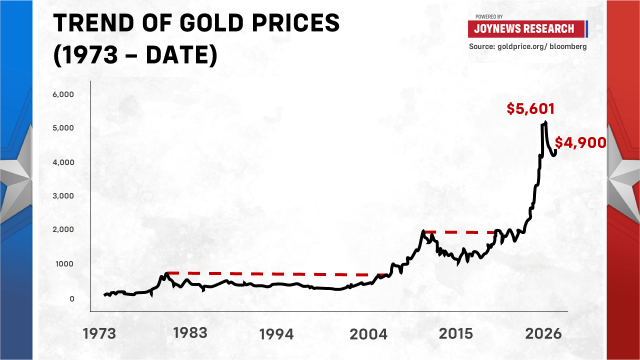

The more immediate driver appears to be gold prices.

Since the return of Donald Trump to the White House, gold prices have risen sharply amid heightened geopolitical and policy uncertainty.

After averaging around $2,300 per ounce in 2024, gold reached highs of about $4,500 in 2025 and has crossed $5,000 per ounce in 2026.

The government is seeking to capture a larger share of this windfall. But setting permanent fiscal policy based on a commodity price boom carries risks.

History shows how quickly gold cycles can turn.

When gold prices surged to about $728 per ounce in 1980, they later collapsed and did not return to that level until 2007, a gap of 27 years.

After rising to nearly $1,800 per ounce in 2011, prices again fell sharply and only recovered in 2020, nine years later.

Ghana’s cocoa sector offers a cautionary example.

Policy was adjusted to take advantage of rising cocoa prices. When prices fell unexpectedly, COCOBOD and farmers were left exposed, with the institution struggling to meet obligations.

A similar approach in gold could leave both the state and mining companies vulnerable when prices eventually retreat.

Official fiscal data from the Chamber of Mines and the Finance Ministry shows that most government revenue from gold comes from corporate income tax, not mineral royalties.

Because royalties are charged on revenue rather than operating income, higher royalty rates reduce operating margins. After expenses, this can shrink taxable profits and ultimately reduce corporate income tax paid to the state.

This raises a critical question.

Has the Lands Ministry modelled whether higher royalties could, over time, reduce overall government revenue by eroding the corporate income tax base?

There is also a behavioural effect.

When gold prices rise, mining companies often expand into higher cost ore bodies that would not be viable at lower prices. This raises operating costs.

Higher royalties applied on revenue, combined with higher costs, further compress operating income. The result is lower taxable profits, reduced reinvestment capacity and weaker incentives for expansion.

Over time, this can deter new investment.

Mining projects are capital intensive and depend on predictable payback periods. If Ghana’s effective tax rate rises too sharply, project economics could deteriorate.

The Ghana Chamber of Mines has modelled the proposed sliding scale and estimates that Ghana’s effective tax rate could rise to between 60% and 68%.

That would place Ghana among the highest taxed mining jurisdictions globally and could materially weaken its competitiveness.

Despite repeated requests, the Lands Ministry has not disclosed whether it has conducted its own fiscal modelling on the impact of the sliding scale on effective tax rates, corporate income tax receipts, investment, industry resilience and long term government revenue.

In the absence of published government analysis, the Chamber’s estimates are currently the only publicly available assessment of the fiscal impact.

An effective tax rate approaching 68% is exceptionally burdensome.

The ministry should publish its fiscal analysis to demonstrate that the policy will not undermine investment or reduce long term government revenue.

This is especially important given that Ghana’s oil production is in decline and the cocoa sector is under strain. Gold and other minerals remain among the few large scale foreign exchange and fiscal anchors.

There has also been limited emphasis so far on value addition, which is a more durable way to increase national benefits from mining.

The Lands Ministry is reportedly working on an overhaul of the Minerals and Mining Act, but no details have been released. Clarity is needed on how reforms will promote local processing, retention of value and insulation from commodity price cycles.

The government has proposed reducing the growth and sustainability levy from 3% to 1% to offer some relief. But without published modelling, it is difficult to assess whether this offsets the impact of higher royalties.

While royalties provide predictable revenue, corporate income tax has consistently been the larger contributor to the state.

As part of broader reform, policymakers should also consider whether aspects of the regime could shift toward profit based mechanisms that better balance state revenue with investment incentives.

Ghana’s cocoa experience shows the dangers of locking in permanent policy responses to temporary price booms. Any overhaul of the mining fiscal regime must be carefully calibrated, with transparent modelling and engagement with industry, to ensure both the state and investors remain viable partners.

The Lands Ministry should publish its fiscal simulations.

That would allow analysts and investors to assess whether the sliding scale indeed strengthens Ghana’s long term position or risks weakening one of the economy’s few remaining pillars.