“Look, if you had one shot or one opportunity to seize everything you ever wanted – One moment.

Would you capture it or just let it slip?”

That is the opening line of US Rapper Eminem’s 2002 hit Lose Yourself.

And 23 years later, this played out perfectly for Ghanaian documentary photographer, Paul Addo, on the hallowed royal durbar grounds of Manhyia in Kumasi, Ashanti Region.

A moment of fatigue became a moment of destiny when he reluctantly grabbed the opportunity to take a shot; unbeknownst to him, that single photo would define his professional journey.

Tired from the intensity of hectic activities, Paul decided to find a spot to rest his feet. That simple act led him to a scene that would forever etch his name into the visual history of the Asante Kingdom.

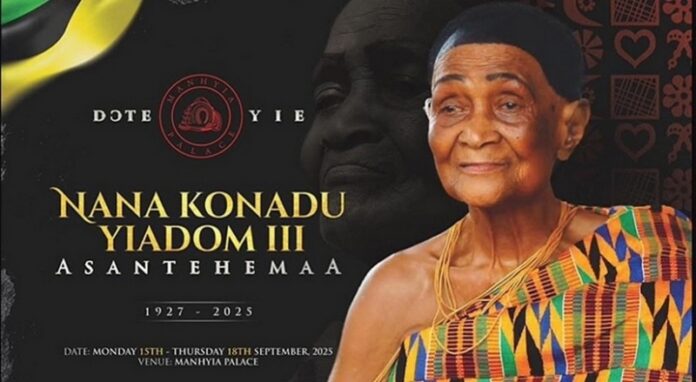

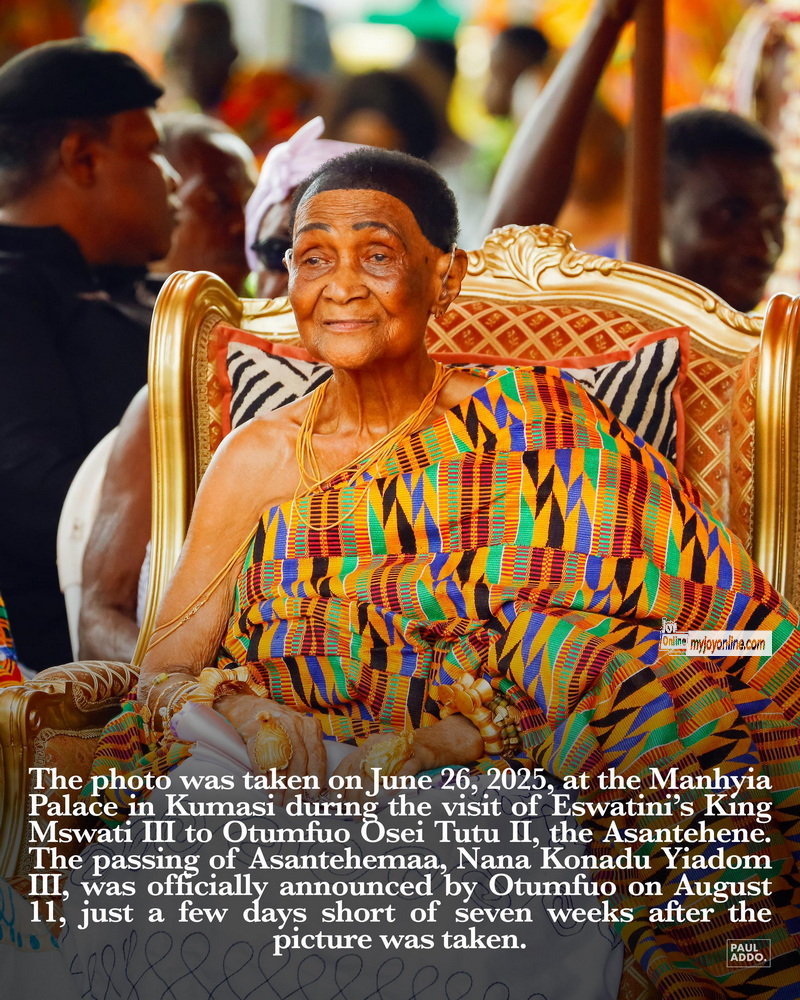

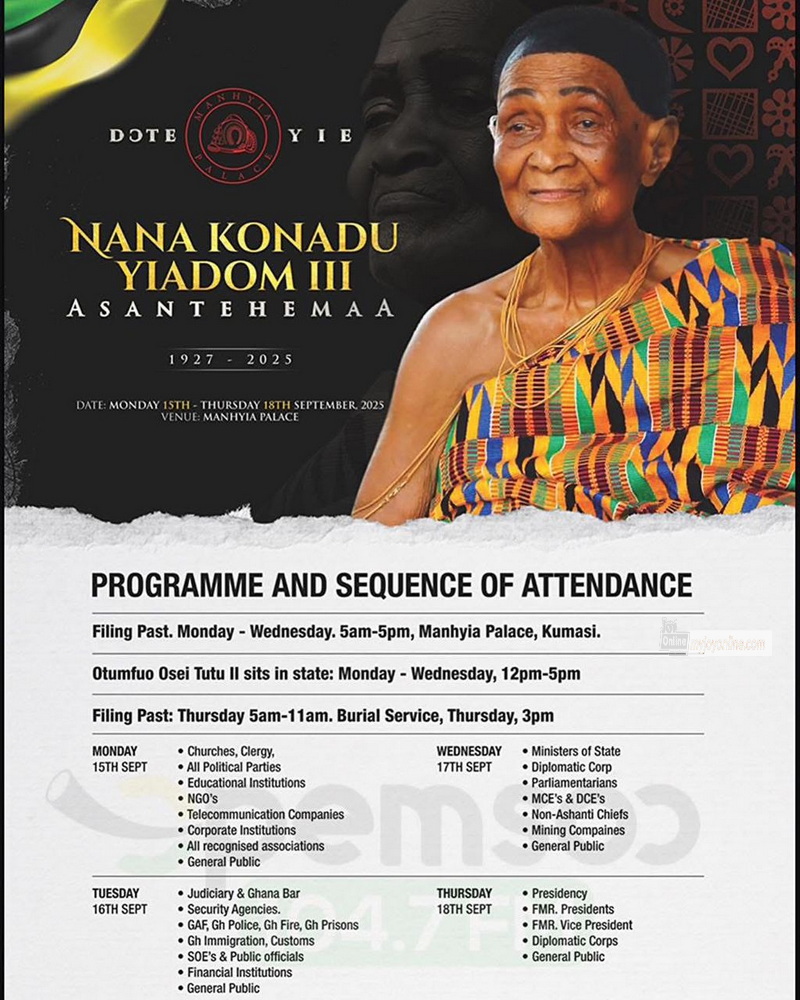

The photograph he took that day, June 26, of the Asantehemaa, Nana Konadu Yiadom III, just seven weeks later, became the official obituary portrait shared across billboards, newspapers, and live broadcasts during the state funeral of the revered queenmother.

The Fateful Day at Manhyia Palace

Paul’s dedication leads him to festivals and royal events across the country, often self-financing his travels.

His account of the day he photographed the Asantehemaa is a masterclass in a photographer’s instinct.

“I was very tired that day; you know how intense these festivals could be. I wanted to go and rest my feet a bit. Just when I was about to move, I saw an all-women group singing and dancing. There weren’t many, and they were right in front of Nana Hemaa. I couldn’t see her directly. I first took a picture of the women singing and dancing, and then, through a small opening, I saw that she was there, sitting under her umbrella.”

Curiosity compelled him to move closer.

“I didn’t know she was the Asantehemaa when I got there, but she was just glowing under her umbrella, and that compelled me to capture her.”

Following an unspoken protocol, he sought permission without words.

“I just bowed slightly to ask for permission and then, with the slightest nod, she agreed. And, you know, she looked me straight into the camera.”

For a few precious seconds, he had her attention.

Then, as she turned to speak with an attendant, Paul continued to shoot, preserving a candid glimpse of royalty.

Paul’s story is one of passion fuelled by perseverance. His advice to aspiring photographers is simple yet powerful:

“You have to shoot all the time… You cannot sit in your room and be thinking or dreaming about a particular shot. You just have to go out, and there you will find the stories, or the stories will find you.”

For Paul Addo, this iconic image is more than a single lucky shot; it is the powerful culmination of a deeply personal mission to tell the Ghanaian story with dignity, beauty, and truth.

How it all began

Paul Addo’s journey into photography began in Ghana’s pulsating music scene, working with platforms like GhanaMusic.com.

It was here, in the world of entertainment and early blogging, that he first encountered the power of an image.

However, the true spark ignited when he stumbled upon the work of a Ghanaian photographer named Yaw Opare online.

“These were pictures from somewhere in the Eastern region… and they were totally different from the regular pictures that I normally see from Ghanaian photographers at the time,” he says. “I had not really seen a photographer moving around the country and taking pictures of the landscape, so when I saw those pictures, it captivated me.”

He reached out, met Yaw Opare, and began studying under him.

Paul Addo is deliberate in calling himself a documentary photographer. His work is not just about capturing news; it’s about telling sustained, beautiful stories. He noticed a glaring disparity between the Ghana he lived in and the Ghana portrayed to the world.

“I realised that, oftentimes, the images that represent us as a country, and if you want to expand it as a continent, it’s not really the reality on the ground,” he explains, his voice firm with conviction. “The beauty within us isn’t shown; it’s not talked about that much. Oftentimes, it’s images of maybe a hungry child or a shirtless child somewhere, and then negative stories. And these are the images that they used to represent us.”

This realisation became the driving force behind his art. He set out to change the narrative, to focus on the profound beauty that resides in Ghana’s landscapes, its vibrant festivals, its rich food culture, and the dignified spirit of its people.

He also speaks candidly about the challenges, especially the business side of photography. He finances his personal projects through commercial gigs, weddings, events, and portraits, a common hustle for artists. But he issues a poignant call for local support, highlighting a critical gap.

“In the developed countries, they have some grants that they give to sponsor photographers to undertake projects. Here in Ghana, I don’t find much of that…,” he laments. I plead with the government and NGO’s to offer their support.”

Looking ahead, Paul Addo’s dreams are as vast as the continent he wishes to document. “I would love to travel the world and have a bigger platform internationally to showcase these works that I’ve been doing in Ghana and in the future Africa as well.”

His campaign remains anchored on a powerful idea, “Telling the Ghanaian story with photographs that dignify us. Not always the negative… we’ve portrayed a negative part of us for more than a hundred years, so we should be able to talk more about the good aspect also.”

Source: Judy Yayra Avanu