As George Weah, at one time named the world’s best footballer, marks a year in power in Liberia the BBC’s Jonathan Paye-Layleh assesses his scorecard.

There is no doubt that at 52, George Weah can still work a crowd.

On New Year’s Eve he invited his cabinet and supporters to the dedication of a private family church that he has had built.

Dressed in white robes, he told the congregation at Forky Jlaleh Family Fellowship Church: “God has given each and every person talent that they can use for their own benefit.”

And he likened the opportunity to serve in his government to be on a football team.

“When you are on the pitch playing you should know there are others on the substitutes’ bench ready to replace you at any time,” he said.

Arsene Wenger honoured

In its end-of-year message, the Liberia Council of Churches summed up the inevitable frustration felt after the euphoria of Mr Weah landslide victory.

“About a year ago, we elected a government with the hope that economically, our lives would be transformed,” Kortu Brown, president of the umbrella Christian group, said on local radio station Prime FM.

The opposition People Unification Party had more of a stark warning for a country still scarred by years of civil war: “At the end of your first year, our people, your people are hungry; the bread and butter issue keeps getting worse

“[A] poorly performed economy is not a good sign for peace and security; when people are hungry they are most definitely angry; Liberia is angry because its people are hungry.”

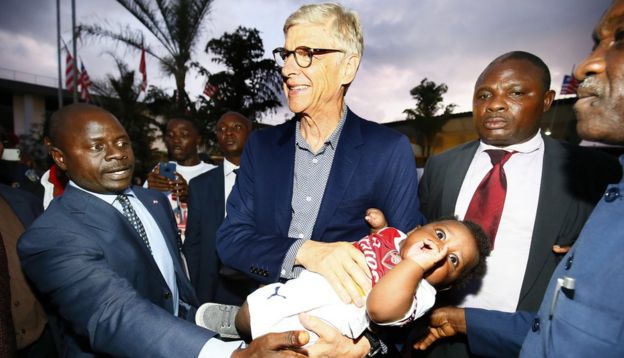

Former Arsenal manager Arsene Wenger was given a hero’s welcome when he visited Liberia

His critics point to one of his first priorities – the retirement of his number 14 shirt, worn during his playing peak – to illustrate what they feel is his lack of vision.

Week-long ceremonies were organised in the capital, Monrovia, with Arsene Wenger, the football coach who had signed him up for Monaco in 1998, being flown over in September and given Liberia’s highest honour.

The president, who retired from football in 2003 to go into politics, played an international friendly as part of the events so the crowds could see him finally hang up the jersey he wore for the national side.

It is easy to see that President Weah is a role model for many young Liberians – growing up in a slum in the capital, Monrovia, becoming one of the world’s most famous footballs stars and then going back to school and university afterwards to finish his education before winning the presidency.

But he faced some immediate criticism for not leading by example in declaring his assets – something all government officials must do before taking office.

After enormous public pressure, he eventually filed a declaration in July – though it has not been published.

The whole saga left questions about his government’s commitment to fighting corruption.

He has also faced accusations about putting his personal business interests first, including pushing ahead with two big real estate projects.

But the chairman of the ruling Congress for Democratic Change party said this proved Liberia was now a good place for good for all investors, and was a good thing for the floundering economy.

“For you to make a determination to invest in a country, you must be guaranteed a security,” Mulbah Morlue was quoted in Liberia’s FrontPage newspaper this month.

“Now, that the man is our president and has created security for all, the guarantee for one to begin to invest in our country is there.”

The president is fond of referring to his football career when trying to motivate people

And the president has been attacked for the personal nature of other public infrastructure projects, from road improvement in his home areas to slum improvements where he grew up.

When he ordered the re-roofing of more than 200 houses in Monrovia’s Gibraltar slum, where he was born and raised, the initial official explanation was that the president was undertaking the project privately and paying for it himself.

But months after the work had been done, a memo to the finance ministry ordering the transfer of nearly $1m (£775,000) in official funds to cover the costs was leaked to the media. The ministry of finance has so far remained silent since the publication of the memo.

Free tuition for university students

Such stories undermine confidence in his authority and make his leadership a constant debate on lively phone-in radio shows.

But he was wildly cheered in October when he announced that tuition fees at state universities and colleges were being scrapped.

However, there are some who fear the decision was not properly considered.

Before the announcement, the University of Liberia was struggling to make ends meet and it currently operates at half of what it needs to function.

Some, including university student leader Martin Kollie, saw it a tactic to distract from the scandal surrounding the allegation that $100m-worth of Liberian currency has gone missing.

In March, stories emerged that the newly printed bank notes intended for the central bank did not reach their destination.

The notes, ordered in November 2017 before Mr Weah took office, allegedly vanished from containers in Monrovia’s port and airport in March, two months after Mr Weah became president.

The government ordered an investigation in September – though that is likely to take months, if not years, to complete – and the journalist who first broke the story has faced death threats.

There have been regular protests under the slogan “Bring Back Our Money”, but central bank governor Nathaniel Patray has denied the money is missing.

But on a personal level, there is no denying that Liberians are having to cope with a severe cash shortage, and people have to queue for hours and sometimes days to withdraw money from banks.

Someone wanting to withdraw, for example, 25,000 Liberian dollars ($160) is given just 5,000 Liberian dollars ($36).

‘I was a performer’

As he inaugurated a community road just before Christmas, Mr Weah roundly rejected those trying to put him down – and said he was used to such pressure.

“Remember I was a performer, I played in front [of] 100,000 people, 200,000 people; if I played bad, they laughed at me; they booed me; but with all the boo and what have you, I still became [the winner of] the Ballon d’Or,” he said in December.

“So anything you say, anything you do to tarnish my reputation – even though I am doing well, you are wasting your time.”

And after nearly a year in power, the president told his congregation as the New Year struck, that it was not a time for despondency: “Let’s forget about all the setbacks in 2018 and focus on the prosperous New Year, what God gave you is enough.”